Это первая часть статьи, посвященной такому языковому механизму Java как исключения (вторая (checked/unchecked) вот). Она имеет вводный характер и рассчитана на начинающих разработчиков или тех, кто только приступает к изучению языка.

Также я веду курс «Scala for Java Developers» на платформе для онлайн-образования udemy.com (аналог Coursera/EdX).

1. Ключевые слова: try, catch, finally, throw, throws

2. Почему используем System.err, а не System.out

3. Компилятор требует вернуть результат (или требует молчать)

4. Нелокальная передача управления (nonlocal control transfer)

5. try + catch (catch — полиморфен)

6. try + catch + catch + …

7. try + finally

8. try + catch + finally

9. Вложенные try + catch + finally

1. Ключевые слова: try, catch, finally, throw, throws

Механизм исключительных ситуаций в Java поддерживается пятью ключевыми словами

- try

- catch

- finally

- throw

- throws

«Магия» (т.е. некоторое поведение никак не отраженное в исходном коде и потому неповторяемое пользователем) исключений #1 заключается в том, что catch, throw, throws можно использовать исключительно с java.lang.Throwable или его потомками.

throws:

Годится

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Throwable {}

}

Не годится

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) throws String {}

}

>> COMPILATION ERROR: Incompatible types: required 'java.lang.Throwable', found: 'java.lang.String'

catch:

Годится

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

} catch (Throwable t) {}

}

}

Не годится

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

} catch (String s) {}

}

}

>> COMPILATION ERROR: Incompatible types: required 'java.lang.Throwable', found: 'java.lang.String'

throw:

Годится

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Error - потомок Throwable

throw new Error();

}

}

Не годится

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

throw new String("Hello!");

}

}

>> COMPILATION ERROR: Incompatible types: required 'java.lang.Throwable', found: 'java.lang.String'

Кроме того, throw требуется не-null аргумент, иначе NullPointerException в момент выполнения

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

throw null;

}

}

>> RUNTIME ERROR: Exception in thread "main" java.lang.NullPointerException

throw и new — это две независимых операции. В следующем коде мы независимо создаем объект исключения и «бросаем» его

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Error ref = new Error(); // создаем экземпляр

throw ref; // "бросаем" его

}

}

>> RUNTIME ERROR: Exception in thread "main" java.lang.Error

Однако, попробуйте проанализировать вот это

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

f(null);

}

public static void f(NullPointerException e) {

try {

throw e;

} catch (NullPointerException npe) {

f(npe);

}

}

}

>> RUNTIME ERROR: Exception in thread "main" java.lang.StackOverflowError

2. Почему используем System.err, а не System.out

System.out — buffered-поток вывода, а System.err — нет. Таким образом вывод может быть как таким

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("sout");

throw new Error();

}

}

>> RUNTIME ERROR: Exception in thread "main" java.lang.Error

>> sout

Так и вот таким (err обогнало out при выводе в консоль)

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("sout");

throw new Error();

}

}

>> sout

>> RUNTIME ERROR: Exception in thread "main" java.lang.Error

Давайте это нарисуем

буфер сообщений

+----------------+

+->| msg2 msg1 msg0 | --> out

/ +----------------+

/ +-> +--------+

ВАШЕ ПРИЛОЖЕНИЕ | КОНСОЛЬ|

+-> +--------+

/

+------------------------> err

нет буфера, сразу печатаем

когда Вы пишете в System.err — ваше сообщение тут же выводится на консоль, но когда пишете в System.out, то оно может на какое-то время быть буферизированно. Stacktrace необработанного исключение выводится через System.err, что позволяет им обгонять «обычные» сообщения.

3. Компилятор требует вернуть результат (или требует молчать)

Если в объявлении метода сказано, что он возвращает НЕ void, то компилятор зорко следит, что бы мы вернули экземпляр требуемого типа или экземпляр типа, который можно неявно привести к требуемому

public class App {

public double sqr(double arg) { // надо double

return arg * arg; // double * double - это double

}

}

public class App {

public double sqr(double arg) { // надо double

int k = 1; // есть int

return k; // можно неявно преобразовать int в double

}

}

// на самом деле, компилятор сгенерирует байт-код для следующих исходников

public class App {

public double sqr(double arg) { // надо double

int k = 1; // есть int

return (double) k; // явное преобразование int в double

}

}

вот так не пройдет (другой тип)

public class App {

public static double sqr(double arg) {

return "hello!";

}

}

>> COMPILATION ERROR: Incompatible types. Required: double. Found: java.lang.String

Вот так не выйдет — нет возврата

public class App {

public static double sqr(double arg) {

}

}

>> COMPILATION ERROR: Missing return statement

и вот так не пройдет (компилятор не может удостовериться, что возврат будет)

public class App {

public static double sqr(double arg) {

if (System.currentTimeMillis() % 2 == 0) {

return arg * arg; // если currentTimeMillis() - четное число, то все ОК

}

// а если нечетное, что нам возвращать?

}

}

>> COMPILATION ERROR: Missing return statement

Компилятор отслеживает, что бы мы что-то вернули, так как иначе непонятно, что должна была бы напечатать данная программа

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

double d = sqr(10.0); // ну, и чему равно d?

System.out.println(d);

}

public static double sqr(double arg) {

// nothing

}

}

>> COMPILATION ERROR: Missing return statement

Из-забавного, можно ничего не возвращать, а «повесить метод»

public class App {

public static double sqr(double arg) {

while (true); // Удивительно, но КОМПИЛИРУЕТСЯ!

}

}

Тут в d никогда ничего не будет присвоено, так как метод sqr повисает

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

double d = sqr(10.0); // sqr - навсегда "повиснет", и

System.out.println(d); // d - НИКОГДА НИЧЕГО НЕ БУДЕТ ПРИСВОЕНО!

}

public static double sqr(double arg) {

while (true); // Вот тут мы на века "повисли"

}

}

Компилятор пропустит «вилку» (таки берем в квадрат ИЛИ висим)

public class App {

public static double sqr(double arg) {

if (System.currentTimeMillis() % 2 == 0) {

return arg * arg; // ну ладно, вот твой double

} else {

while (true); // а тут "виснем" навсегда

}

}

}

Но механизм исключений позволяет НИЧЕГО НЕ ВОЗВРАЩАТЬ!

public class App {

public static double sqr(double arg) {

throw new RuntimeException();

}

}

Итак, у нас есть ТРИ варианта для компилятора

public class App {

public static double sqr(double arg) {// согласно объявлению метода ты должен вернуть double

long time = System.currentTimeMillis();

if (time % 2 == 0) {

return arg * arg; // ок, вот твой double

} else if (time % 2 == 1) { {

while (true); // не, я решил "повиснуть"

} else {

throw new RuntimeException(); // или бросить исключение

}

}

}

Но КАКОЙ ЖЕ double вернет функция, бросающая RuntimeException?

А НИКАКОЙ!

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// sqr - "сломается" (из него "выскочит" исключение),

double d = sqr(10.0); // выполнение метода main() прервется в этой строчке и

// d - НИКОГДА НИЧЕГО НЕ БУДЕТ ПРИСВОЕНО!

System.out.println(d); // и печатать нам ничего не придется!

}

public static double sqr(double arg) {

throw new RuntimeException(); // "бросаем" исключение

}

}

>> RUNTIME ERROR: Exception in thread "main" java.lang.RuntimeException

Подытожим: бросаемое исключение — это дополнительный возвращаемый тип. Если ваш метод объявил, что возвращает double, но у вас нет double — можете бросить исключение. Если ваш метод объявил, что ничего не возвращает (void), но у вам таки есть что сказать — можете бросить исключение.

Давайте рассмотрим некоторый пример из практики.

Задача: реализовать функцию, вычисляющую площадь прямоугольника

public static int area(int width, int height) {...}

важно, что задание звучит именно так, в терминах предметной области — «вычислить площадь прямоугольника», а не в терминах решения «перемножить два числа»:

public static int area(int width, int height) {

return width * height; // тут просто перемножаем

}

Вопрос: что делать, если мы обнаружили, что хотя бы один из аргументов — отрицательное число?

Если просто умножить, то мы пропустили ошибочные данные дальше. Что еще хуже, возможно, мы «исправили ситуацию» — сказали что площадь прямоугольника с двумя отрицательными сторонами -10 и -20 = 200.

Мы не можем ничего не вернуть

public static int area(int width, int height) {

if (width < 0 || height < 0) {

// у вас плохие аргументы, извините

} else {

return width * height;

}

}

>> COMPILATION ERROR: Missing return statement

Можно, конечно, отписаться в консоль, но кто ее будет читать и как определить где была поломка. При чем, вычисление то продолжится с неправильными данными

public static int area(int width, int height) {

if (width < 0 || height < 0) {

System.out.println("Bad ...");

}

return width * height;

}

Можно вернуть специальное значение, показывающее, что что-то не так (error code), но кто гарантирует, что его прочитают, а не просто воспользуются им?

public static int area(int width, int height) {

if (width < 0 || height < 0) {

return -1; // специальное "неправильное" значение площади

}

return width * height;

}

Можем, конечно, целиком остановить виртуальную машину

public static int area(int width, int height) {

if (width < 0 || height < 0) {

System.exit(0);

}

return width * height;

}

Но «правильный путь» таков: если обнаружили возможное некорректное поведение, то

1. Вычисления остановить, сгенерировать сообщение-поломку, которое трудно игнорировать, предоставить пользователю информацию о причине, предоставить пользователю возможность все починить (загрузить белье назад и повторно нажать кнопку старт)

public static int area(int width, int height) {

if (width < 0 || height < 0) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Negative sizes: w = " + width + ", h = " + height);

}

return width * height;

}

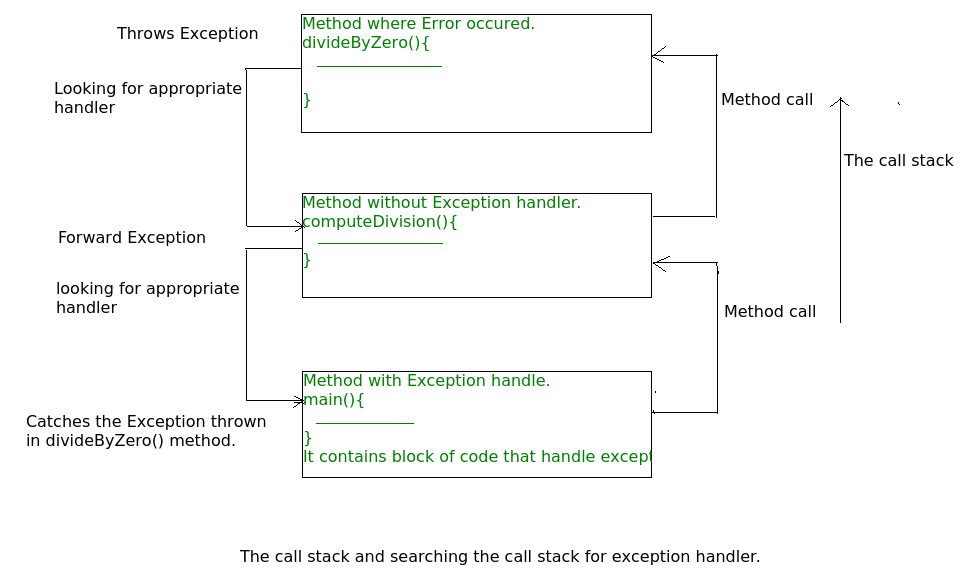

4. Нелокальная передача управления (nonlocal control transfer)

Механизм исключительных ситуация (исключений) — это механизм НЕЛОКАЛЬНОЙ ПЕРЕДАЧИ УПРАВЛЕНИЯ.

Что под этим имеется в виду?

Программа, в ходе своего выполнения (точнее исполнения инструкций в рамках отдельного потока), оперирует стеком («стопкой») фреймов. Передача управления осуществляется либо в рамках одного фрейма

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Пример: ОПЕРАТОР ПОСЛЕДОВАТЕЛЬНОСТИ

int x = 42; // первый шаг

int y = x * x; // второй шаг

x = x * y; // третий шаг

...

}

}

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Пример: ОПЕРАТОР ВЕТВЛЕНИЯ

if (args.length > 2) { первый шаг

// второй шаг или тут

...

} else {

// или тут

...

}

// третий шаг

...

}

}

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Пример: ОПЕРАТОР ЦИКЛА do..while

int x = 1;

do {

...

} while (x++ < 10);

...

}

}

и другие операторы.

Либо передача управления происходит в «стопке» фреймов между СОСЕДНИМИ фреймами

- вызов метода: создаем новый фрейм, помещаем его на верхушку стека и переходим в него

- выход из метода: возвращаемся к предыдущему фрейму (через return или просто кончились инструкции в методе)

return — выходим из ОДНОГО фрейма (из фрейма #4(метод h()))

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.err.println("#1.in");

f(); // создаем фрейм, помещаем в стек, передаем в него управление

System.err.println("#1.out"); // вернулись

} // выходим из текущего фрейма, кончились инструкции

public static void f() {

System.err.println(". #2.in");

g(); // создаем фрейм, помещаем в стек, передаем в него управление

System.err.println(". #2.out"); //вернулись

} // выходим из текущего фрейма, кончились инструкции

public static void g() {

System.err.println(". . #3.in");

h(); // создаем фрейм, помещаем в стек, передаем в него управление

System.err.println(". . #3.out"); // вернулись

} // выходим из текущего фрейма, кончились инструкции

public static void h() {

System.err.println(". . . #4.in");

if (true) {

System.err.println(". . . #4.RETURN");

return; // выходим из текущего фрейма по 'return'

}

System.err.println(". . . #4.out"); // ПРОПУСКАЕМ

}

}

>> #1.in

>> . #2.in

>> . . #3.in

>> . . . #4.in

>> . . . #4.RETURN

>> . . #3.out

>> . #2.out

>> #1.out

throw — выходим из ВСЕХ фреймов

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.err.println("#1.in");

f(); // создаем фрейм, помещаем в стек, передаем в него управление

System.err.println("#1.out"); // ПРОПУСТИЛИ!

}

public static void f() {

System.err.println(". #2.in");

g(); // создаем фрейм, помещаем в стек, передаем в него управление

System.err.println(". #2.out"); // ПРОПУСТИЛИ!

}

public static void g() {

System.err.println(". . #3.in");

h(); // создаем фрейм, помещаем в стек, передаем в него управление

System.err.println(". . #3.out"); // ПРОПУСТИЛИ!

}

public static void h() {

System.err.println(". . . #4.in");

if (true) {

System.err.println(". . . #4.THROW");

throw new Error(); // выходим со всей пачки фреймов ("раскрутка стека") по 'throw'

}

System.err.println(". . . #4.out"); // ПРОПУСТИЛИ!

}

}

>> #1.in

>> . #2.in

>> . . #3.in

>> . . . #4.in

>> . . . #4.THROW

>> RUNTIME ERROR: Exception in thread "main" java.lang.Error

При помощи catch мы можем остановить летящее исключение (причина, по которой мы автоматически покидаем фреймы).

Останавливаем через 3 фрейма, пролетаем фрейм #4(метод h()) + пролетаем фрейм #3(метод g()) + фрейм #2(метод f())

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.err.println("#1.in");

try {

f(); // создаем фрейм, помещаем в стек, передаем в него управление

} catch (Error e) { // "перехватили" "летящее" исключение

System.err.println("#1.CATCH"); // и работаем

}

System.err.println("#1.out"); // работаем дальше

}

public static void f() {

System.err.println(". #2.in");

g(); // создаем фрейм, помещаем в стек, передаем в него управление

System.err.println(". #2.out"); // ПРОПУСТИЛИ!

}

public static void g() {

System.err.println(". . #3.in");

h(); // создаем фрейм, помещаем в стек, передаем в него управление

System.err.println(". . #3.out"); // ПРОПУСТИЛИ!

}

public static void h() {

System.err.println(". . . #4.in");

if (true) {

System.err.println(". . . #4.THROW");

throw new Error(); // выходим со всей пачки фреймов ("раскрутка стека") по 'throw'

}

System.err.println(". . . #4.out"); // ПРОПУСТИЛИ!

}

}

>> #1.in

>> . #2.in

>> . . #3.in

>> . . . #4.in

>> . . . #4.THROW

>> #1.CATCH

>> #1.out

Обратите внимание, стандартный сценарий работы был восстановлен в методе main() (фрейм #1)

Останавливаем через 2 фрейма, пролетаем фрейм #4(метод h()) + пролетаем фрейм #3(метод g())

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.err.println("#1.in");

f(); // создаем фрейм, помещаем в стек, передаем в него управление

System.err.println("#1.out"); // вернулись и работаем

}

public static void f() {

System.err.println(". #2.in");

try {

g(); // создаем фрейм, помещаем в стек, передаем в него управление

} catch (Error e) { // "перехватили" "летящее" исключение

System.err.println(". #2.CATCH"); // и работаем

}

System.err.println(". #2.out"); // работаем дальше

}

public static void g() {

System.err.println(". . #3.in");

h(); // создаем фрейм, помещаем в стек, передаем в него управление

System.err.println(". . #3.out"); // ПРОПУСТИЛИ!

}

public static void h() {

System.err.println(". . . #4.in");

if (true) {

System.err.println(". . . #4.THROW");

throw new Error(); // выходим со всей пачки фреймов ("раскрутка стека") по 'throw'

}

System.err.println(". . . #4.out"); // ПРОПУСТИЛИ!

}

}

>> #1.in

>> . #2.in

>> . . #3.in

>> . . . #4.in

>> . . . #4.THROW

>> . #2.CATCH

>> . #2.out

>> #1.out

Останавливаем через 1 фрейм (фактически аналог return, просто покинули фрейм «другим образом»)

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.err.println("#1.in");

f(); // создаем фрейм, помещаем в стек, передаем в него управление

System.err.println("#1.out"); // вернулись и работаем

}

public static void f() {

System.err.println(". #2.in");

g(); // создаем фрейм, помещаем в стек, передаем в него управление

System.err.println(". #2.out"); // вернулись и работаем

}

public static void g() {

System.err.println(". . #3.in");

try {

h(); // создаем фрейм, помещаем в стек, передаем в него управление

} catch (Error e) { // "перехватили" "летящее" исключение

System.err.println(". . #3.CATCH"); // и работаем

}

System.err.println(". . #3.out"); // работаем дальше

}

public static void h() {

System.err.println(". . . #4.in");

if (true) {

System.err.println(". . . #4.THROW");

throw new Error(); // выходим со всей пачки фреймов ("раскрутка стека") по 'throw'

}

System.err.println(". . . #4.out"); // ПРОПУСТИЛИ!

}

}

>> #1.in

>> . #2.in

>> . . #3.in

>> . . . #4.in

>> . . . #4.THROW

>> . . #3.CATCH

>> . . #3.out

>> . #2.out

>> #1.out

Итак, давайте сведем все на одну картинку

// ---Используем RETURN--- // ---Используем THROW---

// Выход из 1-го фрейма // Выход из ВСЕХ (из 4) фреймов

#1.in #1.in

. #2.in . #2.in

. . #3.in . . #3.in

. . . #4.in . . . #4.in

. . . #4.RETURN . . . #4.THROW

. . #3.out RUNTIME EXCEPTION: Exception in thread "main" java.lang.Error

. #2.out

#1.out

// ---Используем THROW+CATCH---

// Выход из 3-х фреймов // Выход из 2-х фреймов // Выход из 1-го фрейма

#1.in #1.in #1.in

. #2.in . #2.in . #2.in

. . #3.in . . #3.in . . #3.in

. . . #4.in . . . #4.in . . . #4.in

. . . #4.THROW . . . #4.THROW . . . #4.THROW

#1.CATCH . #2.CATCH . . #3.CATCH

#1.out . #2.out . . #3.out

#1.out . #2.out

#1.out

5. try + catch (catch — полиморфен)

Напомним иерархию исключений

Object

|

Throwable

/

Error Exception

|

RuntimeException

То, что исключения являются объектами важно для нас в двух моментах

1. Они образуют иерархию с корнем java.lang.Throwable (java.lang.Object — предок java.lang.Throwable, но Object — уже не исключение)

2. Они могут иметь поля и методы (в этой статье это не будем использовать)

По первому пункту: catch — полиморфная конструкция, т.е. catch по типу Parent перехватывает летящие экземпляры любого типа, который является Parent-ом (т.е. экземпляры непосредственно Parent-а или любого потомка Parent-а)

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

System.err.print(" 0");

if (true) {throw new RuntimeException();}

System.err.print(" 1");

} catch (Exception e) { // catch по Exception ПЕРЕХВАТЫВАЕТ RuntimeException

System.err.print(" 2");

}

System.err.println(" 3");

}

}

>> 0 2 3

Даже так: в блоке catch мы будем иметь ссылку типа Exception на объект типа RuntimeException

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

throw new RuntimeException();

} catch (Exception e) {

if (e instanceof RuntimeException) {

RuntimeException re = (RuntimeException) e;

System.err.print("Это RuntimeException на самом деле!!!");

} else {

System.err.print("В каком смысле не RuntimeException???");

}

}

}

}

>> Это RuntimeException на самом деле!!!

catch по потомку не может поймать предка

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception { // пока игнорируйте 'throws'

try {

System.err.print(" 0");

if (true) {throw new Exception();}

System.err.print(" 1");

} catch (RuntimeException e) {

System.err.print(" 2");

}

System.err.print(" 3");

}

}

>> 0

>> RUNTIME EXCEPTION: Exception in thread "main" java.lang.Exception

catch по одному «брату» не может поймать другого «брата» (Error и Exception не находятся в отношении предок-потомок, они из параллельных веток наследования от Throwable)

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

System.err.print(" 0");

if (true) {throw new Error();}

System.err.print(" 1");

} catch (Exception e) {

System.err.print(" 2");

}

System.err.print(" 3");

}

}

>> 0

>> RUNTIME EXCEPTION: Exception in thread "main" java.lang.Error

По предыдущим примерам — надеюсь вы обратили внимание, что если исключение перехвачено, то JVM выполняет операторы идущие ПОСЛЕ последних скобок try+catch.

Но если не перехвачено, то мы

1. не заходим в блок catch

2. покидаем фрейм метода с летящим исключением

А что будет, если мы зашли в catch, и потом бросили исключение ИЗ catch?

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

System.err.print(" 0");

if (true) {throw new RuntimeException();}

System.err.print(" 1");

} catch (RuntimeException e) { // перехватили RuntimeException

System.err.print(" 2");

if (true) {throw new Error();} // но бросили Error

}

System.err.println(" 3"); // пропускаем - уже летит Error

}

}

>> 0 2

>> RUNTIME EXCEPTION: Exception in thread "main" java.lang.Error

В таком случае выполнение метода тоже прерывается (не печатаем «3»). Новое исключение не имеет никакого отношения к try-catch

Мы можем даже кинуть тот объект, что у нас есть «на руках»

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

System.err.print(" 0");

if (true) {throw new RuntimeException();}

System.err.print(" 1");

} catch (RuntimeException e) { // перехватили RuntimeException

System.err.print(" 2");

if (true) {throw e;} // и бросили ВТОРОЙ раз ЕГО ЖЕ

}

System.err.println(" 3"); // пропускаем - опять летит RuntimeException

}

}

>> 0 2

>> RUNTIME EXCEPTION: Exception in thread "main" java.lang.RuntimeException

И мы не попадем в другие секции catch, если они есть

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

System.err.print(" 0");

if (true) {throw new RuntimeException();}

System.err.print(" 1");

} catch (RuntimeException e) { // перехватили RuntimeException

System.err.print(" 2");

if (true) {throw new Error();} // и бросили новый Error

} catch (Error e) { // хотя есть cath по Error "ниже", но мы в него не попадаем

System.err.print(" 3");

}

System.err.println(" 4");

}

}

>> 0 2

>> RUNTIME EXCEPTION: Exception in thread "main" java.lang.Error

Обратите внимание, мы не напечатали «3», хотя у нас летит Error а «ниже» расположен catch по Error. Но важный момент в том, что catch имеет отношение исключительно к try-секции, но не к другим catch-секциям.

Как покажем ниже — можно строить вложенные конструкции, но вот пример, «исправляющий» эту ситуацию

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

System.err.print(" 0");

if (true) {throw new RuntimeException();}

System.err.print(" 1");

} catch (RuntimeException e) { // перехватили RuntimeException

System.err.print(" 2.1");

try {

System.err.print(" 2.2");

if (true) {throw new Error();} // и бросили новый Error

System.err.print(" 2.3");

} catch (Throwable t) { // перехватили Error

System.err.print(" 2.4");

}

System.err.print(" 2.5");

} catch (Error e) { // хотя есть cath по Error "ниже", но мы в него не попадаем

System.err.print(" 3");

}

System.err.println(" 4");

}

}

>> 0 2.1 2.2 2.4 2.5 4

6. try + catch + catch + …

Как вы видели, мы можем расположить несколько catch после одного try.

Но есть такое правило — нельзя ставить потомка после предка! (RuntimeException после Exception)

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

} catch (Exception e) {

} catch (RuntimeException e) {

}

}

}

>> COMPILATION ERROR: Exception 'java.lang.RuntimeException' has alredy been caught

Ставить брата после брата — можно (RuntimeException после Error)

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

} catch (Error e) {

} catch (RuntimeException e) {

}

}

}

Как происходит выбор «правильного» catch? Да очень просто — JVM идет сверху-вниз до тех пор, пока не найдет такой catch что в нем указано ваше исключение или его предок — туда и заходит. Ниже — не идет.

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

throw new Exception();

} catch (RuntimeException e) {

System.err.println("catch RuntimeException");

} catch (Exception e) {

System.err.println("catch Exception");

} catch (Throwable e) {

System.err.println("catch Throwable");

}

System.err.println("next statement");

}

}

>> catch Exception

>> next statement

Выбор catch осуществляется в runtime (а не в compile-time), значит учитывается не тип ССЫЛКИ (Throwable), а тип ССЫЛАЕМОГО (Exception)

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

Throwable t = new Exception(); // ссылка типа Throwable указывает на объект типа Exception

throw t;

} catch (RuntimeException e) {

System.err.println("catch RuntimeException");

} catch (Exception e) {

System.err.println("catch Exception");

} catch (Throwable e) {

System.err.println("catch Throwable");

}

System.err.println("next statement");

}

}

>> catch Exception

>> next statement

7. try + finally

finally-секция получает управление, если try-блок завершился успешно

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

System.err.println("try");

} finally {

System.err.println("finally");

}

}

}

>> try

>> finally

finally-секция получает управление, даже если try-блок завершился исключением

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

throw new RuntimeException();

} finally {

System.err.println("finally");

}

}

}

>> finally

>> Exception in thread "main" java.lang.RuntimeException

finally-секция получает управление, даже если try-блок завершился директивой выхода из метода

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

return;

} finally {

System.err.println("finally");

}

}

}

>> finally

finally-секция НЕ вызывается только если мы «прибили» JVM

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

System.exit(42);

} finally {

System.err.println("finally");

}

}

}

>> Process finished with exit code 42

System.exit(42) и Runtime.getRuntime().exit(42) — это синонимы

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

Runtime.getRuntime().exit(42);

} finally {

System.err.println("finally");

}

}

}

>> Process finished with exit code 42

И при Runtime.getRuntime().halt(42) — тоже не успевает зайти в finally

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

Runtime.getRuntime().halt(42);

} finally {

System.err.println("finally");

}

}

}

>> Process finished with exit code 42

exit() vs halt()

javadoc: java.lang.Runtime#halt(int status)

… Unlike the exit method, this method does not cause shutdown hooks to be started and does not run uninvoked finalizers if finalization-on-exit has been enabled. If the shutdown sequence has already been initiated then this method does not wait for any running shutdown hooks or finalizers to finish their work.

Однако finally-секция не может «починить» try-блок завершившийся исключение (заметьте, «more» — не выводится в консоль)

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

System.err.println("try");

if (true) {throw new RuntimeException();}

} finally {

System.err.println("finally");

}

System.err.println("more");

}

}

>> try

>> finally

>> Exception in thread "main" java.lang.RuntimeException

Трюк с «if (true) {…}» требуется, так как иначе компилятор обнаруживает недостижимый код (последняя строка) и отказывается его компилировать

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

System.err.println("try");

throw new RuntimeException();

} finally {

System.err.println("finally");

}

System.err.println("more");

}

}

>> COMPILER ERROR: Unrechable statement

И finally-секция не может «предотвратить» выход из метода, если try-блок вызвал return («more» — не выводится в консоль)

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

System.err.println("try");

if (true) {return;}

} finally {

System.err.println("finally");

}

System.err.println("more");

}

}

>> try

>> finally

Однако finally-секция может «перебить» throw/return при помощи другого throw/return

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.err.println(f());

}

public static int f() {

try {

return 0;

} finally {

return 1;

}

}

}

>> 1

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.err.println(f());

}

public static int f() {

try {

throw new RuntimeException();

} finally {

return 1;

}

}

}

>> 1

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.err.println(f());

}

public static int f() {

try {

return 0;

} finally {

throw new RuntimeException();

}

}

}

>> Exception in thread "main" java.lang.RuntimeException

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.err.println(f());

}

public static int f() {

try {

throw new Error();

} finally {

throw new RuntimeException();

}

}

}

>> Exception in thread "main" java.lang.RuntimeException

finally-секция может быть использована для завершающего действия, которое гарантированно будет вызвано (даже если было брошено исключение или автор использовал return) по окончании работы

// open some resource

try {

// use resource

} finally {

// close resource

}

Например для освобождения захваченной блокировки

Lock lock = new ReentrantLock();

...

lock.lock();

try {

// some code

} finally {

lock.unlock();

}

Или для закрытия открытого файлового потока

InputStream input = new FileInputStream("...");

try {

// some code

} finally {

input.close();

}

Специально для этих целей в Java 7 появилась конструкция try-with-resources, ее мы изучим позже.

Вообще говоря, в finally-секция нельзя стандартно узнать было ли исключение.

Конечно, можно постараться написать свой «велосипед»

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.err.println(f());

}

public static int f() {

long rnd = System.currenttimeMillis();

boolean finished = false;

try {

if (rnd % 3 == 0) {

throw new Error();

} else if (rnd % 3 == 1) {

throw new RuntimeException();

} else {

// nothing

}

finished = true;

} finally {

if (finished) {

// не было исключений

} else {

// было исключение, но какое?

}

}

}

}

Не рекомендуемые практики

— return из finally-секции (можем затереть исключение из try-блока)

— действия в finally-секции, которые могут бросить исключение (можем затереть исключение из try-блока)

8. try + catch + finally

Нет исключения

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

System.err.print(" 0");

// nothing

System.err.print(" 1");

} catch(Error e) {

System.err.print(" 2");

} finally {

System.err.print(" 3");

}

System.err.print(" 4");

}

}

>> 0 1 3 4

Не заходим в catch, заходим в finally, продолжаем после оператора

Есть исключение и есть подходящий catch

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

System.err.print(" 0");

if (true) {throw new Error();}

System.err.print(" 1");

} catch(Error e) {

System.err.print(" 2");

} finally {

System.err.print(" 3");

}

System.err.print(" 4");

}

}

>> 0 2 3 4

Заходим в catch, заходим в finally, продолжаем после оператора

Есть исключение но нет подходящего catch

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

System.err.print(" 0");

if (true) {throw new RuntimeException();}

System.err.print(" 1");

} catch(Error e) {

System.err.print(" 2");

} finally {

System.err.print(" 3");

}

System.err.print(" 4");

}

}

>> 0 3

>> RUNTIME ERROR: Exception in thread "main" java.lang.RuntimeException

Не заходим в catch, заходим в finally, не продолжаем после оператора — вылетаем с неперехваченным исключением

9. Вложенные try + catch + finally

Операторы обычно допускают неограниченное вложение.

Пример с if

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

if (args.length > 1) {

if (args.length > 2) {

if (args.length > 3) {

...

}

}

}

}

}

Пример с for

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < 10; i++) {

for (int k = 0; k < 10; k++) {

...

}

}

}

}

}

Суть в том, что try-cacth-finally тоже допускает неограниченное вложение.

Например вот так

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

try {

try {

...

} catch (Exception e) {

} finally {}

} catch (Exception e) {

} finally {}

} catch (Exception e) {

} finally {}

}

}

Или даже вот так

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

try {

...

} catch (Exception e) {

...

} finally {

...

}

} catch (Exception e) {

try {

...

} catch (Exception e) {

...

} finally {

...

}

} finally {

try {

...

} catch (Exception e) {

...

} finally {

...

}

}

}

}

Ну что же, давайте исследуем как это работает.

Вложенный try-catch-finally без исключения

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

System.err.print(" 0");

try {

System.err.print(" 1");

// НИЧЕГО

System.err.print(" 2");

} catch (RuntimeException e) {

System.err.print(" 3"); // НЕ заходим - нет исключения

} finally {

System.err.print(" 4"); // заходим всегда

}

System.err.print(" 5"); // заходим - выполнение в норме

} catch (Exception e) {

System.err.print(" 6"); // НЕ заходим - нет исключения

} finally {

System.err.print(" 7"); // заходим всегда

}

System.err.print(" 8"); // заходим - выполнение в норме

}

}

>> 0 1 2 4 5 7 8

Мы НЕ заходим в обе catch-секции (нет исключения), заходим в обе finally-секции и выполняем обе строки ПОСЛЕ finally.

Вложенный try-catch-finally с исключением, которое ПЕРЕХВАТИТ ВНУТРЕННИЙ catch

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

System.err.print(" 0");

try {

System.err.print(" 1");

if (true) {throw new RuntimeException();}

System.err.print(" 2");

} catch (RuntimeException e) {

System.err.print(" 3"); // ЗАХОДИМ - есть исключение

} finally {

System.err.print(" 4"); // заходим всегда

}

System.err.print(" 5"); // заходим - выполнение УЖЕ в норме

} catch (Exception e) {

System.err.print(" 6"); // не заходим - нет исключения, УЖЕ перехвачено

} finally {

System.err.print(" 7"); // заходим всегда

}

System.err.print(" 8"); // заходим - выполнение УЖЕ в норме

}

}

>> 0 1 3 4 5 7 8

Мы заходим в ПЕРВУЮ catch-секцию (печатаем «3»), но НЕ заходим во ВТОРУЮ catch-секцию (НЕ печатаем «6», так как исключение УЖЕ перехвачено первым catch), заходим в обе finally-секции (печатаем «4» и «7»), в обоих случаях выполняем код после finally (печатаем «5»и «8», так как исключение остановлено еще первым catch).

Вложенный try-catch-finally с исключением, которое ПЕРЕХВАТИТ ВНЕШНИЙ catch

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

System.err.print(" 0");

try {

System.err.print(" 1");

if (true) {throw new Exception();}

System.err.print(" 2");

} catch (RuntimeException e) {

System.err.print(" 3"); // НЕ заходим - есть исключение, но НЕПОДХОДЯЩЕГО ТИПА

} finally {

System.err.print(" 4"); // заходим всегда

}

System.err.print(" 5"); // не заходим - выполнение НЕ в норме

} catch (Exception e) {

System.err.print(" 6"); // ЗАХОДИМ - есть подходящее исключение

} finally {

System.err.print(" 7"); // заходим всегда

}

System.err.print(" 8"); // заходим - выполнение УЖЕ в норме

}

}

>> 0 1 4 6 7 8

Мы НЕ заходим в ПЕРВУЮ catch-секцию (не печатаем «3»), но заходим в ВТОРУЮ catch-секцию (печатаем «6»), заходим в обе finally-секции (печатаем «4» и «7»), в ПЕРВОМ случае НЕ выполняем код ПОСЛЕ finally (не печатаем «5», так как исключение НЕ остановлено), во ВТОРОМ случае выполняем код после finally (печатаем «8», так как исключение остановлено).

Вложенный try-catch-finally с исключением, которое НИКТО НЕ ПЕРЕХВАТИТ

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

System.err.print(" 0");

try {

System.err.print(" 1");

if (true) {throw new Error();}

System.err.print(" 2");

} catch (RuntimeException e) {

System.err.print(" 3"); // НЕ заходим - есть исключение, но НЕПОДХОДЯЩЕГО ТИПА

} finally {

System.err.print(" 4"); // заходим всегда

}

System.err.print(" 5"); // НЕ заходим - выполнение НЕ в норме

} catch (Exception e) {

System.err.print(" 6"); // не заходим - есть исключение, но НЕПОДХОДЯЩЕГО ТИПА

} finally {

System.err.print(" 7"); // заходим всегда

}

System.err.print(" 8"); // не заходим - выполнение НЕ в норме

}

}

>> 0 1 4 7

>> RUNTIME EXCEPTION: Exception in thread "main" java.lang.Error

Мы НЕ заходим в ОБЕ catch-секции (не печатаем «3» и «6»), заходим в обе finally-секции (печатаем «4» и «7») и в обоих случаях НЕ выполняем код ПОСЛЕ finally (не печатаем «5» и «8», так как исключение НЕ остановлено), выполнение метода прерывается по исключению.

Контакты

Я занимаюсь онлайн обучением Java (вот курсы программирования) и публикую часть учебных материалов в рамках переработки курса Java Core. Видеозаписи лекций в аудитории Вы можете увидеть на youtube-канале, возможно, видео канала лучше систематизировано в этой статье.

Мой метод обучения состоит в том, что я

- показываю различные варианты применения

- строю усложняющуюся последовательность примеров по каждому варианту

- объясняю логику двигавшую авторами (по мере возможности)

- даю большое количество тестов (50-100) всесторонне проверяющее понимание и демонстрирующих различные комбинации

- даю лабораторные для самостоятельной работы

Данная статье следует пунктам #1 (различные варианты) и #2(последовательность примеров по каждому варианту).

skype: GolovachCourses

email: GolovachCourses@gmail.com

As developers, we would like our users to interact with applications that run smoothly and without issues. We want the libraries that we create to be widely adopted and successful. All of that will not happen without the code that handles errors.

Java exception handling is often a significant part of the application code. You might use conditionals to handle cases where you expect a certain state and want to avoid erroneous execution – for example, division by zero. However, there are cases where conditions are not known or are well hidden because of third party code. In other cases, code is designed to create an exception and throw it up the stack to allow for the graceful handling of a Java error at a higher level.

If all this is new to you, this tutorial will help you understand what Java exceptions are, how to handle them and the best practices you should follow to maintain the natural flow of the application.

What Is an Exception in Java?

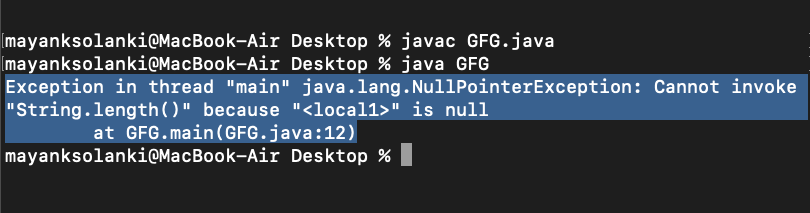

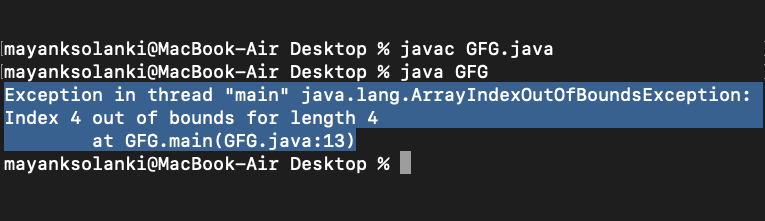

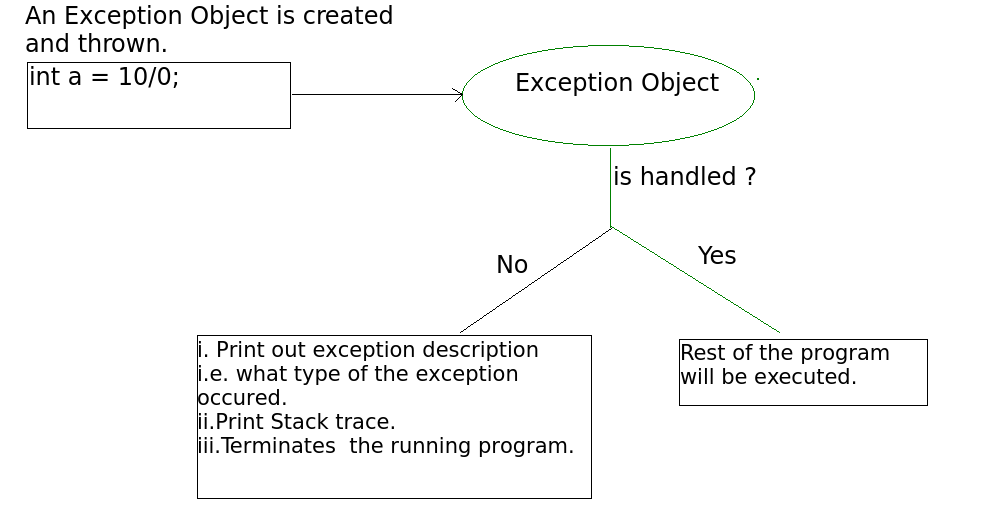

An Exception is an event that causes your normal Java application flow to be disrupted. Exceptions can be caused by using a reference that is not yet initialized, dividing by zero, going beyond the length of an array, or even JVM not being able to assign objects on the heap.

In Java, an exception is an Object that wraps the error that caused it and includes information like:

- The type of error that caused the exception with the information about it.

- The stack trace of the method calls.

- Additional custom information that is related to the error.

Various Java libraries throw exceptions when they hit a state of execution that shouldn’t happen – from the standard Java SDK to the enormous amounts of open source code that is available as a third-party library.

Exceptions can be created automatically by the JVM that is running our code or explicitly our code itself. We can extend the classes that are responsible for exceptions and create our own, specific Java exceptions that handle unexpected situations. But keep in mind that throwing an exception doesn’t come for free. It is expensive. The larger the call stack the more expensive the exception.

Exception handling in Java is a mechanism to process, catch and throw Java errors that signal an abnormal state of the program so that the execution of the business code can continue uninterrupted.

Why Handle Java Exceptions?

Using Java exceptions is very handy; they let you separate the business logic from the application code for handling errors. However, exceptions are neither free nor cheap. Throwing an exception requires the JVM to perform operations like gathering the full stack trace of the method calls and passing it to the method that is responsible for handling the exception. In other words, it requires additional resources compared to a simple conditional.

No matter how expensive the exceptions are, they are invaluable for troubleshooting issues. Correlating exceptions with other data like JVM metrics and various application logs can help with resolving your problems fast and in a very efficient manner.

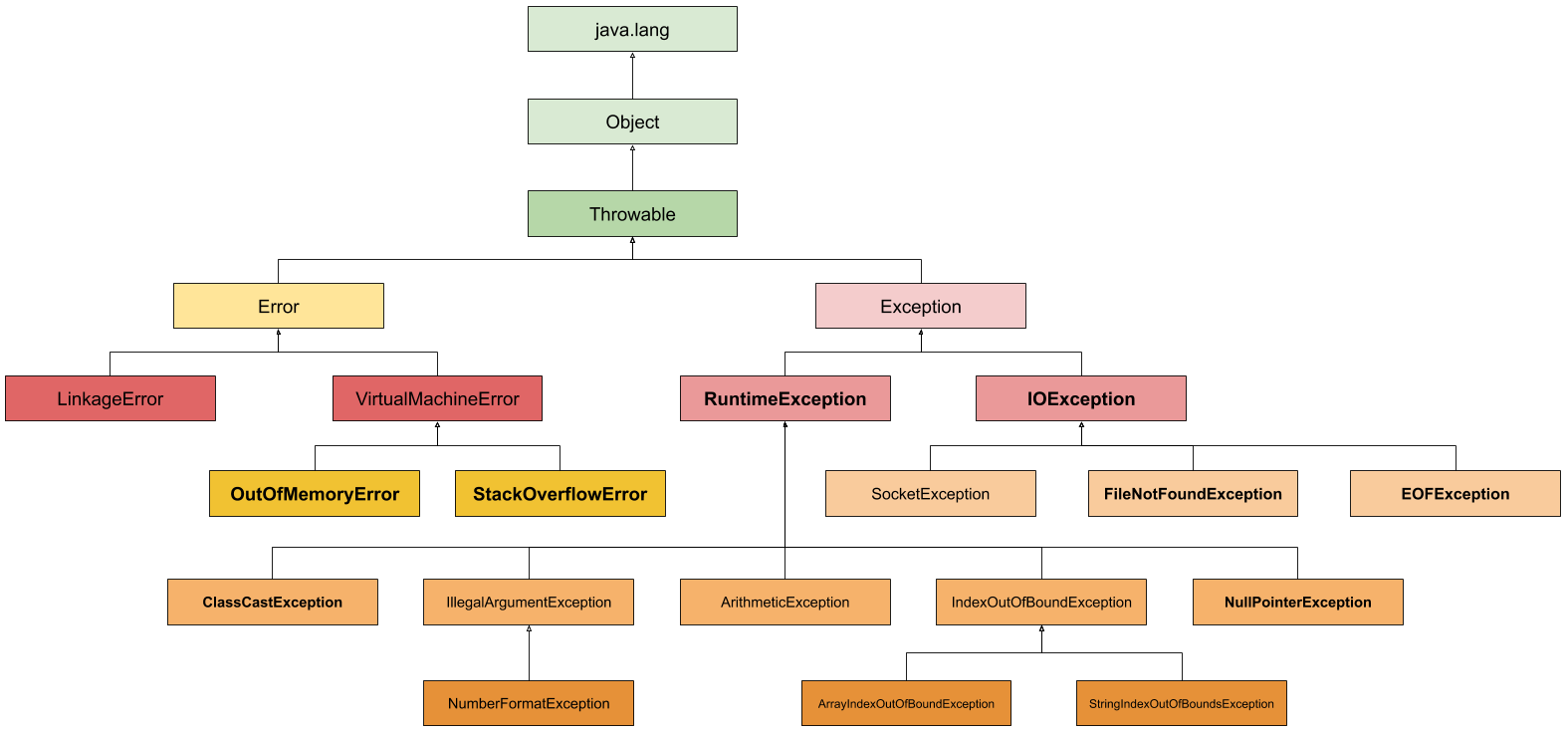

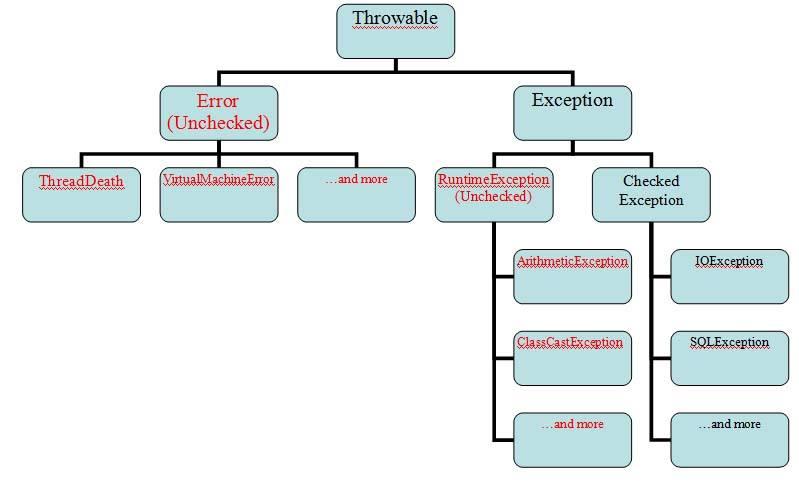

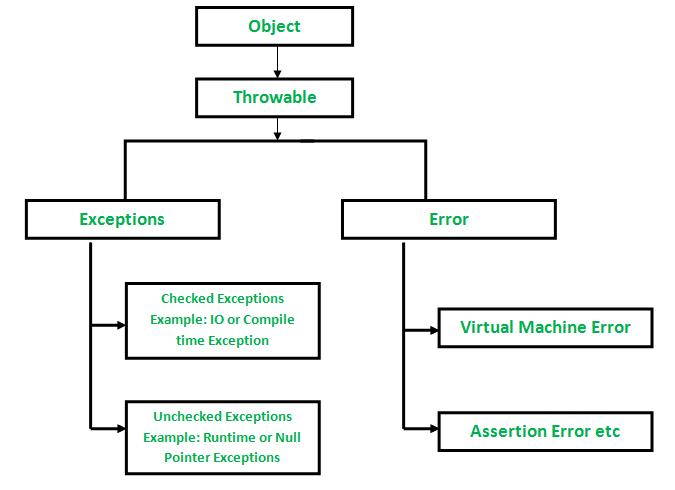

Exception Class Hierarchy

Java is an object-oriented language, and thus, every class will extend the java.lang.Object. The same goes for the Throwable class, which is the base class for the errors and exceptions in Java. The following picture illustrates the class hierarchy of the Throwable class and its most common subclasses:

The Difference Between a Java Exception and Error

Before going into details about the Exception class, we should ask one fundamental question: What is the difference between an Error and an Exception in Java?

To answer the question, let’s look at Javadocs and start from the Throwable class. The Throwable class is the mother of all errors–the superclass of all errors and exceptions that your Java code can produce. Only objects that are instances of the Throwable class or any of its subclasses can be thrown by the code running inside the JVM or can be declared in the methods throw clause. There are two main implementations of the Throwable class.

A Java Error is a subclass of Throwable that represents a serious problem that a reasonable application should not try to catch. The method does not have to declare an Error or any of its subclasses in its throws clause for it to be thrown during the execution of a method. The most common subclasses of the Error class are Java OutOfMemoryError and StackOverflowError classes. The first one represents JVM not being able to create a new object; we discussed potential causes in our article about the JVM garbage collector. The second error represents an issue when the application recurses too deeply.

The Java Exception and its subclasses, on the other hand, represent situations that an application should catch and try to handle. There are lots of implementations of the Exception class that represent situations that your application can gracefully handle. The FileNotFoundException, SocketException, or NullPointerException are just a few examples that you’ve probably come across when writing Java applications.

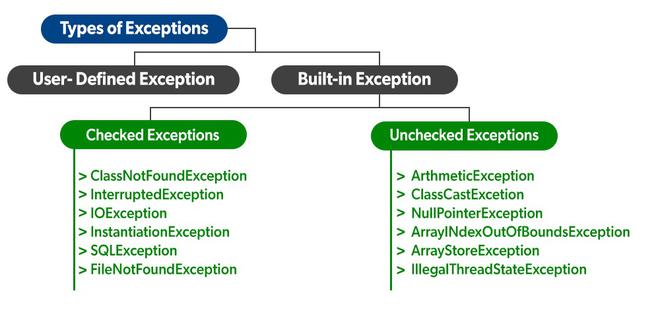

Types of Java Exceptions

There are multiple implementations of the Exception class in Java. They come from the Java Development Kit itself, but also from various libraries and applications that you might be using when writing your own code. We will not discuss every Exception subclass that you can encounter, but there are two main types that you should be aware of to understand how exception handling works in Java–the checked and unchecked, aka runtime exceptions.

Checked Exceptions

The Java checked exceptions are the ones that implement the Exception class and not the RuntimeException. They are called checked exceptions because the compiler verifies them during the compile-time and refuses to compile the code if such exceptions are not handled or declared. Instead, the compiler will notify you to handle these exceptions. For example, the FileNotFoundException is an example of such an exception.

In order for a method or constructor to throw a checked exception it needs to be explicitly declared:

public CheckedExceptions() throws FileNotFoundException {

throw new FileNotFoundException("File not found");

}

public void throwsExample() throws FileNotFoundException {

throw new FileNotFoundException("File not found");

}

You can see that in both cases we explicitly have the throws clause mentioning the FileNotFoundException that can be thrown by the execution of the constructor of the throwsExample method. Such code will be successfully compiled and can be executed.

On the other hand, the following code will not compile:

public void wrongThrowsExample() {

throw new FileNotFoundException("File not found");

}

The reason for the compiler not wanting to compile the above code will be raising the checked exception and not processing it. We need to either include the throws clause or handle the Java exception in the try/catch/finally block. If we were to try to compile the above code as is the following error would be returned by the compiler:

/src/main/java/com/sematext/blog/java/CheckedExceptions.java:18: error: unreported exception FileNotFoundException; must be caught or declared to be thrown

throw new FileNotFoundException("File not found");

^

Unchecked Exceptions / Runtime Exceptions

The unchecked exceptions are exceptions that the Java compiler does not require us to handle. The unchecked exceptions in Java are the ones that implement the RuntimeException class. Those exceptions can be thrown during the normal operation of the Java Virtual Machine. Unchecked exceptions do not need to be declared in the method throws clause in order to be thrown. For example, this block of code will compile and run without issues:

public class UncheckedExceptions {

public static void main(String[] args) {

UncheckedExceptions ue = new UncheckedExceptions();

ue.run();

}

public void run() {

throwRuntimeException();

}

public void throwRuntimeException() {

throw new NullPointerException("Null pointer");

}

}

We create an UncheckedExceptions class instance and run the run method. The run method calls the throwRuntimeException method which creates a new NullPointerException. Because the NullPointerException is a subclass of the RuntimeException we don’t need to declare it in the throws clause.

The code compiles and propagates the exception up to the main method. We can see that in the output when the code is run:

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.NullPointerException: Null pointer

at com.sematext.blog.java.UncheckedExceptions.throwRuntimeException(UncheckedExceptions.java:14)

at com.sematext.blog.java.UncheckedExceptions.run(UncheckedExceptions.java:10)

at com.sematext.blog.java.UncheckedExceptions.main(UncheckedExceptions.java:6)

This is exactly what we expected.

The most common subclasses of the Java RuntimeException that you probably saw already are ClassCastException, ConcurrentModificationException, IllegalArgumentException, or everyone’s favorite, NullPointerException.

Let’s now look at how we throw exceptions in Java.

How to Handle Exceptions in Java: Code Examples

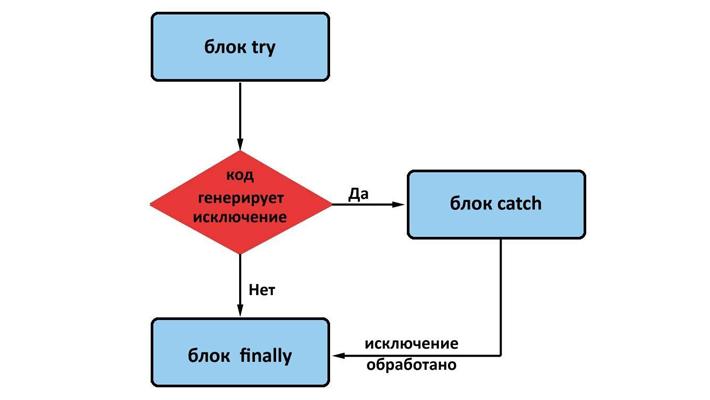

Handling exceptions in Java is a game of using five keywords that combined give us the possibility of handling errors – the try, catch, finally, throw, and throws.

The first one – try is used to specify the block of code that can throw an exception:

try {

File file = openNewFileThatMayNotExists(location);

// process the file

}

The try block must be followed by the catch or finally blocks. The first one mentioned can be used to catch and process exceptions thrown in the try block:

try {

...

} catch (IOException ioe) {

// handle missing file

}

The finally block can be used to handle the code that needs to be executed regardless of whether the exception happened or not.

The throw keyword is used to create a new Exception instance and the throws keyword is used to declare what kind of exceptions can be expected when executing a method.

When handling exceptions in Java, we don’t want to just throw the created exception to the top of the call stack, for example, to the main method. That would mean that each and every exception that is thrown would crash the application and this is not what should happen. Instead, we want to handle Java exceptions, at least the ones that we can deal with, and either help fixing the problem or fail gracefully.

Java gives us several ways to handle exceptions.

Throwing Exceptions

An Exception in Java can be handled by using the throw keyword and creating a new Exception or re-throwing an already created exception. For example, the following very naive and simple method creates an instance of the File class and checks if the file exists. If the file doesn’t exist the method throws a new IOException:

public File openFile(String path) throws IOException {

File file = new File(path);

if (!file.exists()) {

throw new IOException(String.format("File %s doesn't exist", path));

}

// continue execution of the business logic

return file;

}

You can also re-throw a Java exception that was thrown inside the method you are executing. This can be done by the try-catch block:

public class RethrowException {

public static void main(String[] args) throws IOException {

RethrowException exec = new RethrowException();

exec.run();

}

public void run() throws IOException {

try {

methodThrowingIOE();

} catch (IOException ioe) {

// do something about the exception

throw ioe;

}

}

public void methodThrowingIOE() throws IOException {

throw new IOException();

}

}

You can see that the run method re-throws the IOException that is created in the methodThrowingIOE. If you plan on doing some processing of the exception, you can catch it as in the above example and throw it further. However, keep in mind that in most cases, this is not a good practice. You shouldn’t catch the exception, process it, and push it up the execution stack. If you can’t process it, it is usually better to pack it into a more specialized Exception class, so that a dedicated error processing code can take care of it. You can also just decide that you can’t process it and just throw it:

public class RethrowException {

public static void main(String[] args) throws IOException {

RethrowException exec = new RethrowException();

exec.run();

}

public void run() throws IOException {

try {

methodThrowingIOE();

} catch (IOException ioe) {

throw ioe;

}

}

public void methodThrowingIOE() throws IOException {

throw new IOException();

}

}

There are additional cases, but we will discuss them when talking about how to catch exceptions in Java.

Try-Catch Block

The simplest and most basic way to handle exceptions is to use the try – catch block. The code that can throw an exception is put into the try block and the code that should handle it is in the catch block. The exception can be either checked or unchecked. In the first case, the compiler will tell you which kind of exceptions need to be caught or defined in the method throws clause for the code to compile. In the case of unchecked exceptions, we are not obligated to catch them, but it may be a good idea – at least in some cases. For example, there is a DOMException or DateTimeException that indicate issues that you can gracefully handle.

To handle the exception, the code that might generate an exception should be placed in the try block which should be followed by the catch block. For example, let’s look at the code of the following openFileReader method:

public Reader openFileReader(String filePath) {

try {

return new FileReader(filePath);

} catch (FileNotFoundException ffe) {

// tell the user that the file was not found

}

return null;

}

The method tries to create a FileReader class instance. The constructor of that class can throw a checked FileNotFoundException if the file provided as the argument doesn’t exist. We could just include the FileNotFoundException in the throws clause of our openFileReader method or catch it in the catch section just like we did. In the catch section, we can do whatever we need to get a new file location, create a new file, and so on.

If we would like to just throw it further up the call stack the code could be further simplified:

public Reader openFileReaderWithThrows(String filePath) throws FileNotFoundException {

return new FileReader(filePath);

}

This passes the responsibility of handling the FIleNotFoundException to the code that calls it.

Multiple Catch Block

We are not limited to a single catch block in the try-catch block. We can have multiple try-catch blocks that allow you to handle each exception differently, would you need that. Let’s say that we have a method that lists more than a single Java exception in its throws clause, like this:

public void readAndParse(String file) throws FileNotFoundException, ParseException {

// some business code

}

In order to compile and run this we need multiple catch blocks to handle each of the listed Java exceptions:

public void run(String file) {

try {

readAndParse(file);

} catch (FileNotFoundException ex) {

// do something when file is not found

} catch (ParseException ex) {

// do something if the parsing fails

}

}

Such code organization can be used when dealing with multiple Java exceptions that need to be handled differently. Hypothetically, the above code could ask for a new file location when the FileNotFoundException happens and inform the user of the issues with parsing when the ParseException happens.

There is one more thing we should mention when it comes to handle exceptons using multiple catch blocks. You need to remember that the order of the catch blocks matters. If you have a more specialized Java exception in the catch block after the more general exception the more specialized catch block will never be executed. Let’s look at the following example:

public void runTwo(String file) {

try {

readAndParse(file);

} catch (Exception ex) {

// this block will catch all exceptions

} catch (ParseException ex) {

// this block will not be executed

}

}

Because the first catch block catches the Java Exception the catch block with the ParseException will never be executed. That’s because the ParseException is a subclass of the Exception.

Catching Multiple Exceptions

To handle multiple Java exceptions with the same logic, you can list them all inside a single catch block. Let’s redo the above example with the FileNotFoundException and the ParseException to use a single catch block:

public void runSingleCatch(String file) {

try {

readAndParse(file);

} catch (FileNotFoundException | ParseException ex) {

// do something when file is not found

}

}

You can see how easy it is–you can connect multiple Java exceptions together using the | character. If any of these exceptions is thrown in the try block the execution will continue inside the catch block.

The Finally Block

In addition to try and the catch blocks, there is one additional section that may come in handy when handling exceptions in Java–the finally block. The finally block is the last section in your try-catch-finally expression and will always get executed–either after the try or after the catch. It will be executed even if you use the return statement in the try block, which by the way, you shouldn’t do.

Let’s look at the following example:

public void exampleOne() {

FileReader reader = null;

try {

reader = new FileReader("/tmp/somefile");

// do some processing

} catch (FileNotFoundException ex) {

// do something

} finally {

if (reader != null) {

try {

reader.close();

} catch (IOException ex) {

// do something

}

}

}

}

You can see the finally block. Keep in mind that you can have at most one finally block present. The way this code will be executed is as follows:

- The JVM will execute the try section first and will try to create the FileReader instance.

- If the /tmp/somefile is present and readable the try block execution will continue.

- If the /tmp/somefile is not present or is not readable the FileNotFoundException will be raised and the execution of the code will go to the catch block.

- After 2) or 3) the finally block will be executed and will try to close the FileReader instance if it is present.

The finally section will be executed even if we modify the try block and include the return statement. The following code does exactly the same as the one above despite having the return statement at the end of the try block:

public void exampleOne() {

FileReader reader = null;

try {

reader = new FileReader("/tmp/somefile");

// do something

return;

} catch (FileNotFoundException ex) {

// do something

} finally {

if (reader != null) {

try {

reader.close();

} catch (IOException ex) {

// do something

}

}

}

}

So, why and when should you use the finally block to handle exceptions in Java? Well, it is a perfect candidate for cleaning up resources, like closing objects, calculating metrics, including Java logs about operation completion, and so on.

The Try-With-Resources Block

The last thing when it comes to handling exceptions in Java is the try-with-resources block. The idea behind that Java language structure is opening resources in the try section that will be automatically closed at the end of the statement. That means that instead of including the finally block we can just open the resources that we need in the try section and rely on the Java Virtual Machine to deal with the closing of the resource.

For the class to be usable in the try-with-resource block it needs to implement the java.lang.AutoCloseable, which includes every class implementing the java.io.Closeable interface. Keep that in mind.

An example method that reads a file using the FileReader class which uses the try-with-resources might look as follows:

public void readFile(String filePath) {

try (FileReader reader = new FileReader(filePath)) {

// do something

} catch (FileNotFoundException ex) {

// do something when file is not found

} catch (IOException ex) {

// do something when issues during reader close happens

}

}

Of course, we are not limited to a single resource and we can have multiple of them, for example:

public void readFiles(String filePathOne, String filePathTwo) {

try (

FileReader readerOne = new FileReader(filePathOne);

FileReader readerTwo = new FileReader(filePathTwo);

) {

// do something

} catch (FileNotFoundException ex) {

// do something when file is not found

} catch (IOException ex) {

// do something when issues during reader close happens

}

}

One thing that you have to remember is that you need to process the Java exceptions that happen during resources closing in the catch section of the try-catch-finally block. That’s why in the above examples, we’ve included the IOException in addition to the FileNotFoundException. The IOException may be thrown during FileReader closing and we need to process it.

Catching User-Defined Exceptions

The Throwable and Exception are Java classes and so you can easily extend them and create your own exceptions. Depending on if you need a checked or unchecked exception you can either extend the Exception or the RuntimeException class. To give you a very simple example on how such code might look like, have a look at the following fragment:

public class OwnExceptionExample {

public void doSomething() throws MyOwnException {

// code with very important logic

throw new MyOwnException("My Own Exception!");

}

class MyOwnException extends Exception {

public MyOwnException(String message) {

super(message);

}

}

}

In the above trivial example we have a new Java Exception implementation called MyOwnException with a constructor that takes a single argument – a message. It is an internal class, but usually you would just move it to an appropriate package and start using it in your application code.

How to Catch Specific Java Exceptions

Catching specific Java exceptions is not very different from handling a general exception. Let’s look at the code examples. Catching exceptions that implement the Exception class is as simple as having a code similar to the following one:

try {

// code that can result in exception throwing

} catch (Exception ex) {

// handle exception

}

The catch block in the above example would run for every object implementing the Exception class. These include IOException, EOFException, FileNotFoundException, or the NullPointerException. But sometimes we may want to have different behavior depending on the exception that was thrown. You may want different behavior for the IOException and different for the FileNotFoundException. This can be achieved by having multiple catch blocks:

try {

// code that can result in exception throwing

} catch (FileNotFoundException ex) {

// handle exception

} catch (IOException ex) {

// handle exception

}

There is one thing to remember though. The first catch clause that will match the exception class will be executed. The FileNotFoundException is a subclass of the IOException. That’s why I specified the FileNotFoundException as the first one. If I would do the opposite, the block with the IOException handling would catch all IOException instances and their subclasses. Something worth remembering.

Finally, we’ve mentioned that before, but I wanted to repeat myself here – if you would like to handle numerous exceptions with the same code you can do that by combining them in a single catch block:

try {

// code that can result in exception throwing

} catch (FileNotFoundException | EOFException ex) {

// handle exception

} catch (IOException ex) {

// handle exception

}

That way you don’t have to duplicate the code.

Java Exception Handling Best Practices

There are a lot of best practices when it comes to handling exceptions in the Java Virtual Machine world, but I find a few of them useful and important.

Keep Exceptions Use to a Minimum

Every time you throw an Exception it needs to be handled by the JVM. Throwing an exception doesn’t cost much, but for example, getting the stack trace for the exception is noticeable, especially when you deal with a large number of concurrent requests and get the stack trace for every exception.

What I will say is not true for every situation and for sure makes the code a bit uglier, but if you want to squeeze every bit of performance from your code, try to avoid Java exceptions when a simple comparison is enough. Look at the following method:

public int divide(int dividend, int divisor) {

try {

return dividend / divisor;

} catch (ArithmeticException ex) {

LOG.error("Error while division, stack trace:", ex.getStackTrace());

}

return -1;

}

It tries to divide two numbers and catches the ArithmeticException in case of a Java error. What kind of error can happen here? Well, division by zero is the perfect example. If the divisor argument is 0 the code will throw an exception, catch it to avoid failure in the code and continue returning -1. This is not the perfect way to go since throwing a Java exception has a performance penalty – we talk about it later in the blog post. In such cases, you should check the divisor argument and allow the division only if it is not equal to 0, just like this:

public int divide(int dividend, int divisor) {

if (divisor != 0) {

return 10 / divisor;

}

return -1;

}

The performance of throwing an exception is not high, but parts of the error handling code may be expensive – for example stack trace retrieval. Keep that in mind when writing your code that handles Java exceptions and situations that should not be allowed.

Always Handle Exceptions, Don’t Ignore Them

Always handle the Java Exception, unless you don’t care about one. But if you think that you should ignore one, think twice. The methods that you call throw exceptions for a reason and you may want to process them to avoid problematic situations.

Process the exceptions, log them, or just print them to the console. Avoid doing things you can see in the following code:

try {

FileReader reader = new FileReader(filePath);

// some business code

} catch (FileNotFoundException ex) {}

As you can see in the code above the FileNotFoundException is hidden and we don’t have any idea that the creation of the FileReader failed. Of course, the code that runs after the creation of the FileReader would probably fail if it were to operate on that. Now imagine that you are catching Java exceptions like this:

try {

FileReader reader = new FileReader(filePath);

// some business code

} catch (Exception ex) {}

You would catch lots of Java exceptions and completely ignore them all. The least you would like to do is fail and log the information so that you can easily find the problem when doing log analysis or setting up an alert in your log centralization solution. Of course, you may want to process the exception, maybe do some interaction with external systems or the user itself, but for sure not hide the problem.

If you really don’t want to handle an exception in Java you can just print it to the log or error stream, for example:

try {

FileReader reader = new FileReader(filePath);

// some business code

} catch (Exception ex) {

ex.printStackTrace();

}

Or even better, if you are using a centralized logging solution just do the following to store the error log there:

try {

FileReader reader = new FileReader(filePath);

// some business code

} catch (Exception ex) {

LOG.error("Error during FileReader creation", ex);

}

Use Descriptive Messages When Throwing Exceptions

When using exceptions, think about the person who will be looking at the logs or will be troubleshooting your application. Think about what kind of information will be needed to quickly and efficiently find the root cause of the problem – Java exceptions in our case.

When throwing an exception you can use code like this:

throw new FileNotFoundException(“file not found”);

Or code that looks like this:

throw new FileNotFoundException(String.format(“File %s not found in directory %s”, file, directory));

The first one will just say that some mystery file was not found. The person that will try to diagnose and fix the problem will not know which and where the file is expected to be. The second example explicitly mentions which file is expected and where – and it is exactly what you should do when throwing exceptions.

Never Use Return Statement in the Finally Block

The finally block is the place in which you can execute code regardless if the exception happened or not – for example close the opened resources to avoid leaks. The next thing you should avoid is using the return statement in the finally block of your code. Have a look at the following code fragment:

public class ReturnInFinally {

public static void main(String[] args) {

ReturnInFinally app = new ReturnInFinally();

app.example();

System.out.println("Ended without error");

}

public void example() {

try {

throw new NullPointerException();

} finally {

return;

}

}

}

If you were to run it, it would end up printing the Ended without error to the console. But we did throw the NullPointerException, didn’t we? Yes, but that would be hidden because of our finally block. We didn’t catch the exception and according to Java language Exception handling specification, the exception would just be discarded. We don’t want something like that to happen, because that would mean that we are hiding issues in the code and its execution.

Never Use Throw Statement in the Finally Block

A very similar situation to the one above is when you try to throw a new Java Exception in the finally block. Again, the code speaks louder than a thousand words, so let’s have a look at the following example:

public class ThrowInFinally {

public static void main(String[] args) {

ThrowInFinally app = new ThrowInFinally();

app.example();

}

public void example() {

try {

throw new RuntimeException("Exception in try");

} finally {

throw new RuntimeException("Exception in finally");

}

}

}

If you were to execute the above code the sentence that will be printed in the error console would be the following:

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.RuntimeException: Exception in finally at com.sematext.blog.java.ThrowInFinally.example(ThrowInFinally.java:13) at com.sematext.blog.java.ThrowInFinally.main(ThrowInFinally.java:6)

Yes, it is true. The Java RuntimeException that was thrown in the try block will be hidden and the one that was thrown in the finally block will take its place. It may not seem big, but have a look at the code like this:

public void example() throws Exception {

FileReader reader = null;

try {

reader = new FileReader("/tmp/somefile");

} finally {

reader.close();

}

}

Now think about the execution of the code and what happens in a case where the file specified by the filePath is not available. First, the FileReader constructor would throw a FileNotFoundException and the execution would jump to the finally block. Once it gets there it would try to call the close method on a reference that is null. That means that the NullPointerException would be thrown here and the whole example method would throw it. So practically, the FileNotFoundException would be hidden and thus the real problem would not be easily visible that well.

Performance Side Effects of Using and Handling Exceptions in Java

We’ve mentioned that using exceptions in Java doesn’t come for free. Throwing an exception requires the JVM to fill up the whole call trace, list each method that comes with it, and pass it further to the code that will finally catch and handle the Java exception. That’s why you shouldn’t use exceptions unless it is really necessary.

Let’s look at a very simple test. We will run two classes–one will do the division by zero and catch the exception that is caused by that operation. The other code will check if the divisor is zero before throwing the exception. The mentioned code is encapsulated in a method.

The code that uses an exception looks as follows:

public int divide(int dividend, int divisor) {

try {

return dividend / divisor;

} catch (Exception ex) {

// handle exception

}

return -1;

}

The code that does a simple check using a conditional looks as follows:

public int divide(int dividend, int divisor) {

if (divisor != 0) {

return 10 / divisor;

}

return -1;

}

One million executions of the first method take 15 milliseconds, while one million executions of the second method take 5 milliseconds. So you can clearly see that there is a large difference in the execution time when running the code with exceptions and when using a simple conditional to check if the execution should be allowed. Of course, keep in mind that this comparison is very, very simple, and doesn’t reflect real-world scenarios, but it should give you an idea of what to expect when crafting your own code.

The test execution time will differ depending on the machine, but you can run it on your own if you would like by cloning this Github repository.

Troubleshooting Java Exceptions with Sematext