Состояние

потока может быть проверено с помощью

битов класса ios

— базового для классов istream,

ostream

и iostream,

которые

использe.ncz

для ввода-вывода.

Ошибки

потока:

Бит

eofbit

для

входного потока автоматически

устанавливается, когда встречается

признак конца файла. Используется для

определения в потоке признака конца

файла. Вызов cin.eof()

(возвращает true,

если

в cin

встретился признак конца файла, и false

в

противном случае).

Бит

failbit

устанавливается

для потока, если в потоке происходит

ошибка форматирования, но символы не

утеряны (обычно данные можно восстановить)

— пользовательская

ошибка.

Бит

badbit

устанавливается

для потока при возникновении ошибки,

к-ая приводит к потере данных (выполнена

недопустимая опер-я).Данные

обычно не восстанавливаются.

Бит

goodbit

устанавливается

для потока, если ни один из битов eofbit,

failbit

и badbit

не

установлен (нет

никаких ошибок).

Возвращает true,

если

для данного потока все ф-ции bad,

fail

и

eof

должны

вернуть false.

Функция-элемент

rdstate

возвращает

состояние ошибки потока (читает

состояние потока).

Функция-элемент

clear

обычно

используется для восстановления потока

в нормальное состояние (когда

функция-элемент good

возвращает

истину), при котором можно продолжать

операции ввода-вывода данного потока.

По умолчанию параметр функции clear

принимает значение ios::goodbit,

так что оператор

cin.clear();

очистит входной поток cin

и установит goodbit

для этого потока. Оператор

cin.clear(ios::failbit)устанавливает

failbit.

Функция-элемент

operator!

возвращает

истину в том случае, если установлен

либо badbit,

либо

failbit,

либо

оба вместе. Функция-элемент operator

void

*

возвращает false,

если

установлен либо badbit,

либо

failbit,

либо

оба вместе. Эти функции полезны при

обработке файлов и проверке истинности

или ложности условия в структуре выбора

или в структуре повторения.

Hardfail

– неисправимая ошибка

Функция

eof()

возвр int,

если eofbit

Fail()

возвр

истину

если

Failbit

Badbit Hardfail

Good()

возвр истину если ошибок не было

Вопрос 39. Понятие исключения. Когда должна использоваться обработка исключений.

Обработка

исключений позволяет отловить ошибку

перед её возникновением.

Обработка исключений используются в

том случае, когда система может

восстановиться из состояния ошибки.

Т.е. обработчик исключений является

процедурой восстановления. Исключения

– возникновение непредвиденных

ошибочных условий, например, деление

на 0,… Обычно эти условия завершают

выполнение программы системной ошибкой.

Но возможно восстановить программу из

этих условий и продолжать её выполнение.

Обработка

исключений позволяет внести отслеживание

потенциально возможных ошибок вне

основного кода программы.

Наиболее

типичные ошибки, обрабатываемые с

помощью исключений:

-

неуспешное

выполнение new -

выход

интерфейса за пределы массива -

деление

на 0 -

неправильные

аргументы при вызове ф-ций

Обработка

исключений должна использоваться для:

-

обработки

только исключительных ситуаций. -

обработки

исключения, возникающие в тех компонентах

программы, к-ые сами не имеют механизма

обработки этих исключений. -

обработки

исключения, возникающие в таких

компонентах программы, как ф-ции,

библиотеки и классы, к-ые широко

используются, и в к-ых не имеет смысла

вводить собственную обработку

исключений. -

обработки

больших проектов (ошибки, возникающие

в различных местах проекта, обрабатываются

одинаковым способом).

Добавлено 9 октября 2021 в 21:35

Состояния потока

Класс ios_base содержит несколько флагов состояния, которые используются для сигнализации различных условий, которые могут возникнуть при использовании потоков:

| Флаг | Назначение |

|---|---|

goodbit |

Всё в порядке |

badbit |

Произошла какая-то фатальная ошибка (например, программа попыталась прочитать после конца файла) |

eofbit |

Поток достиг конца файла |

failbit |

Произошла нефатальная ошибка (например, пользователь ввел буквы, когда программа ожидала целое число) |

Хотя эти флаги находятся в ios_base, но поскольку ios является производным от ios_base, а ios требует меньше ввода текста, чем ios_base, доступ к ним обычно осуществляется через него (например, как std::ios::failbit).

ios также предоставляет ряд функций-членов для удобного доступа к этим состояниям:

| Функция-член | Назначение |

|---|---|

good() |

Возвращает true, если установлен goodbit (поток в норме) |

bad() |

Возвращает true, если установлен badbit (произошла фатальная ошибка) |

eof() |

Возвращает true, если установлен eofbit (поток находится в конце файла) |

fail() |

Возвращает true, если установлен failbit (произошла нефатальная ошибка) |

clear() |

Очищает все флаги и восстанавливает поток в состояние goodbit |

clear(state) |

Очищает все флаги и устанавливает флаг состояния, переданный в параметре |

rdstate() |

Возвращает текущие установленные флаги |

setstate(state) |

Устанавливает флаг состояния, переданный в параметре |

Чаще всего мы имеем дело failbit, который устанавливается, когда пользователь вводит недопустимые входные данные. Например, рассмотрим следующую программу:

std::cout << "Enter your age: ";

int age;

std::cin >> age;Обратите внимание, что эта программа ожидает, что пользователь введет целое число. Однако если пользователь вводит нечисловые данные, такие как «Alex«, cin не сможет извлечь что-либо для переменной возраста age, и будет установлен бит отказа failbit.

Если такая ошибка возникает, и для потока устанавливается значение, отличное от goodbit, дальнейшие операции с этим потоком будут проигнорированы. Это условие можно устранить, вызвав функцию clear().

Проверка корректности входных данных

Валидация (проверка корректности) входных данных – это процесс проверки того, соответствует ли пользовательский ввод некоторому набору критериев. Валидацию ввода обычно можно разделить на два типа: строковую и числовую.

При проверке строки мы принимаем весь пользовательский ввод как строку, а затем принимаем или отклоняем эту строку в зависимости от того, правильно ли она отформатирована. Например, если мы просим пользователя ввести номер телефона, мы можем проверить, что вводимые данные содержат десять цифр. В большинстве языков (особенно в скриптовых языках, таких как Perl и PHP) это делается с помощью регулярных выражений. Стандартная библиотека C++ также имеет библиотеку регулярных выражений. Регулярные выражения медленны по сравнению с проверкой строк вручную, и их следует использовать только в том случае, если производительность (время компиляции и время выполнения) не вызывает беспокойства, или ручная проверка слишком обременительна.

При числовой проверке мы обычно заботимся о том, чтобы число, вводимое пользователем, находилось в определенном диапазоне (например, от 0 до 20). Однако, в отличие от проверки строк, пользователь может вводить вещи, которые вообще не являются цифрами, и нам также необходимо обрабатывать эти случаи.

Чтобы помочь нам, C++ предоставляет ряд полезных функций, которые мы можем использовать для определения того, являются ли конкретные символы цифрами или буквами. В заголовке cctype находятся следующие функции:

| Функция | Назначение |

|---|---|

std::isalnum(int) |

Возвращает ненулевое значение, если параметр представляет собой букву или цифру. |

std::isalpha(int) |

Возвращает ненулевое значение, если параметр представляет собой букву. |

std::iscntrl(int) |

Возвращает ненулевое значение, если параметр является управляющим символом. |

std::isdigit(int) |

Возвращает ненулевое значение, если параметр является цифрой. |

std::isgraph(int) |

Возвращает ненулевое значение, если параметр является печатным символом, который не является пробелом. |

std::isprint(int) |

Возвращает ненулевое значение, если параметр является печатным символом (включая пробелы). |

std::ispunct(int) |

Возвращает ненулевое значение, если параметр не является ни буквенно-цифровым, ни пробельным символом. |

std::isspace(int) |

Возвращает ненулевое значение, если параметр – пробельный символ. |

std::isxdigit(int) |

Возвращает ненулевое значение, если параметр является шестнадцатеричной цифрой (0-9, a-f, A-F). |

Проверка строки

Примечание автора

С этого момента мы будем использовать функции, которые (пока) не описаны в этой серии статей. Если вы хорошо разбираетесь в C++, возможно, вы сможете понять, что делают эти функции, исходя из их названий и того, как они используются. Советуем посмотреть эти новые функции и типы в справочнике, чтобы лучше понять, что они делают, и для чего еще их можно использовать.

Давайте рассмотрим простой случай проверки строки, попросив пользователя ввести свое имя. Нашим критерием проверки будет то, что пользователь вводит только буквенные символы или пробелы. Если встретится что-то еще, ввод будет отклонен.

Когда дело доходит до входных данных переменной длины, лучший способ проверить строку (помимо использования библиотеки регулярных выражений) – это пройти по всем символам строки и убедиться, что они соответствует критериям проверки. Это именно то, что мы собираемся здесь сделать, или, лучше сказать, то, что std::all_of сделает для нас.

#include <algorithm> // std::all_of

#include <cctype> // std::isalpha, std::isspace

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <string_view>

bool isValidName(std::string_view name)

{

return std::ranges::all_of(name, [](char ch) {

return (std::isalpha(ch) || std::isspace(ch));

});

// До C++20, без диапазонов ranges

// return std::all_of(name.begin(), name.end(), [](char ch) {

// return (std::isalpha(ch) || std::isspace(ch));

// });

}

int main()

{

std::string name{};

do

{

std::cout << "Enter your name: ";

std::getline(std::cin, name); // получаем всю строку, включая пробелы

} while (!isValidName(name));

std::cout << "Hello " << name << "!n";

}Обратите внимание, что этот код не идеален: пользователь мог сказать, что его имя «asf w jweo s di we ao«, или какая-то другая тарабарщина, или, что еще хуже, просто несколько пробелов. Мы могли бы решить эту проблему, уточнив наши критерии проверки, чтобы принимать только строки, содержащие хотя бы один символ и не более одного пробела.

Теперь давайте рассмотрим другой пример, в котором мы попросим пользователя ввести свой номер телефона. В отличие от имени пользователя, которое имеет переменную длину и критерии проверки одинаковы для каждого символа, номер телефона имеет фиксированную длину, но критерии проверки различаются в зависимости от положения символа. Следовательно, для валидации нам необходим другой подход. В этом случае мы собираемся написать функцию, которая будет проверять данные, введенные пользователем, на соответствие заранее определенному шаблону, чтобы увидеть, соответствует ли они ему. Шаблон будет работать следующим образом:

- # будет соответствовать любой цифре в данных, введенных пользователем;

- @ будет соответствовать любому буквенному символу в пользовательском вводе;

- _ будет соответствовать любому пробельному символу;

- ? будет соответствовать чему угодно;

- в противном случае символы в данных, введенных пользователем, и в шаблоне должны точно совпадать.

Итак, если мы спрашиваем функцию, соответствует ли строка шаблону «(###) ###-####«, это означает, что мы ожидаем, что пользователь введет символ ‘(‘, три цифры, символ ‘)‘, пробел, три числа, дефис и еще четыре числа. Если что-либо из этого не совпадает, ввод будет отклонен.

Вот код:

#include <algorithm> // std::equal

#include <cctype> // std::isdigit, std::isspace, std::isalpha

#include <iostream>

#include <map>

#include <string>

#include <string_view>

bool inputMatches(std::string_view input, std::string_view pattern)

{

if (input.length() != pattern.length())

{

return false;

}

// Мы должны использовать указатель на функцию в стиле C,

// потому что у std::isdigit и других есть перегрузки,

// и иначе вызовы будут неоднозначными.

static const std::map<char, int (*)(int)> validators{

{ '#', &std::isdigit },

{ '_', &std::isspace },

{ '@', &std::isalpha },

{ '?', [](int) { return 1; } }

};

// До C++20 используйте следующее

// return std::equal(input.begin(), input.end(), pattern.begin(), [](char ch, char mask) -> bool {

// ...

return std::ranges::equal(input, pattern, [](char ch, char mask) -> bool {

if (auto found{ validators.find(mask) }; found != validators.end())

{

// Текущий элемент шаблона был найден в validators.

// Вызов соответствующей функции.

return (*found->second)(ch);

}

else

{

// Текущий элемент шаблона не найден в validators.

// Символы должны точно совпадать.

return (ch == mask);

}

});

}

int main()

{

std::string phoneNumber{};

do

{

std::cout << "Enter a phone number (###) ###-####: ";

std::getline(std::cin, phoneNumber);

} while (!inputMatches(phoneNumber, "(###) ###-####"));

std::cout << "You entered: " << phoneNumber << 'n';

}Используя эту функцию, мы можем заставить пользователя вводить данные, точно соответствующие нашему конкретному формату. Однако эта функция всё еще имеет несколько ограничений: Если #, @, _ и ? являются допустимыми символами в пользовательском вводе, эта функция не будет работать, потому что этим символам присвоено особое значение. Кроме того, в отличие от регулярных выражений, здесь нет шаблонного символа, означающего, что «можно ввести переменное количество символов». Таким образом, такой шаблон нельзя использовать для обеспечения того, чтобы пользователь вводил два слова, разделенных пробелом, поскольку он не может обработать тот факт, что слова имеют переменную длину. Для таких задач, как правило, более уместен нешаблонный подход.

Проверка чисел

При работе с числовым вводом очевидный способ обработки – использовать оператор извлечения для извлечения входных данных в переменную числового типа. Проверяя бит отказа (failbit), мы можем определить, ввел ли пользователь число или нет.

Давайте попробуем такой подход:

#include <iostream>

#include <limits>

int main()

{

int age{};

while (true)

{

std::cout << "Enter your age: ";

std::cin >> age;

if (std::cin.fail()) // извлечение не производилось

{

// сбрасываем биты состояния обратно в goodbit,

// чтобы мы могли использовать ignore()

std::cin.clear();

// очищаем недопустимый ввод из потока

std::cin.ignore(std::numeric_limits<std::streamsize>::max(), 'n');

// попробовать снова

continue;

}

if (age <= 0) // убедиться, что значение возраста положительное

continue;

break;

}

std::cout << "You entered: " << age << 'n';

}Если пользователь вводит число, cin.fail() вернет false, и мы перейдем к инструкции break, выходя из цикла. Если пользователь вводит данные, начинающиеся с буквы, cin.fail() вернет true, и мы перейдем к условному выражению.

Однако есть еще один случай, который мы не проверили, и это когда пользователь вводит строку, которая начинается с цифр, но затем содержит буквы (например, «34abcd56«). В этом случае начальные числа (34) будут извлечены в переменную age, а остаток строки («abcd56«) останется во входном потоке, и бит отказа НЕ будет установлен. Это вызывает две потенциальные проблемы:

- если вы хотите, чтобы это был допустимый ввод, теперь в вашем потоке есть мусор;

- если вы не хотите, чтобы это был допустимый ввод, он не отклоняется (и в вашем потоке есть мусор);

Решим первую проблему. Это просто:

#include <iostream>

#include <limits>

int main()

{

int age{};

while (true)

{

std::cout << "Enter your age: ";

std::cin >> age;

if (std::cin.fail()) // извлечение не производилось

{

// сбрасываем биты состояния обратно в goodbit,

// чтобы мы могли использовать ignore()

std::cin.clear();

// очищаем недопустимый ввод из потока

std::cin.ignore(std::numeric_limits<std::streamsize>::max(), 'n');

// попробовать снова

continue;

}

// очищаем любой дополнительный ввод из потока

std::cin.ignore(std::numeric_limits<std::streamsize>::max(), 'n');

if (age <= 0) // убедиться, что значение возраста положительное

continue;

break;

}

std::cout << "You entered: " << age << 'n';

}Если вы не хотите, чтобы такие данные были допустимыми, нам придется проделать небольшую дополнительную работу. К счастью, предыдущее решение помогает нам в этом. Мы можем использовать функцию gcount(), чтобы определить, сколько символов было проигнорировано. Если наш ввод был допустимым, gcount() должна вернуть 1 (отброшенный символ новой строки). Если она возвращает больше 1, пользователь ввел что-то, что не было извлечено правильно, и мы должны попросить его ввести новые данные. Ниже показан пример этого:

#include <iostream>

#include <limits>

int main()

{

int age{};

while (true)

{

std::cout << "Enter your age: ";

std::cin >> age;

if (std::cin.fail()) // извлечение не производилось

{

// сбрасываем биты состояния обратно в goodbit,

// чтобы мы могли использовать ignore()

std::cin.clear();

// очищаем недопустимый ввод из потока

std::cin.ignore(std::numeric_limits<std::streamsize>::max(), 'n');

// попробовать снова

continue;

}

// очищаем любой дополнительный ввод из потока

std::cin.ignore(std::numeric_limits<std::streamsize>::max(), 'n');

if (std::cin.gcount() > 1) // если мы удалили более одного дополнительного символа

{

continue; // будем считать этот ввод недопустимым

}

if (age <= 0) // убедиться, что значение возраста положительное

{

continue;

}

break;

}

std::cout << "You entered: " << age << 'n';

}Проверка чисел в виде строки

В приведенном выше примере потребовалось довольно много работы, чтобы просто получить простое значение! Другой способ обработки числовых входных данных – прочитать их как строку, а затем попытаться преобразовать в переменную числового типа. Следующая программа использует этот метод:

#include <charconv> // std::from_chars

#include <iostream>

#include <optional>

#include <string>

#include <string_view>

std::optional<int> extractAge(std::string_view age)

{

int result{};

auto end{ age.data() + age.length() };

// Пытаемся извлечь int из строки age

if (std::from_chars(age.data(), end, result).ptr != end)

{

return {};

}

if (result <= 0) // убедиться, что значение возраста положительное

{

return {};

}

return result;

}

int main()

{

int age{};

while (true)

{

std::cout << "Enter your age: ";

std::string strAge{};

std::cin >> strAge;

if (auto extracted{ extractAge(strAge) })

{

age = *extracted;

break;

}

}

std::cout << "You entered: " << age << 'n';

}Будет ли этот подход более или менее трудоемким, чем извлечение чисел напрямую, зависит от ваших параметров проверки и ограничений.

Как видите, проверка ввода в C++ – это большая работа. К счастью, многие такие задачи (например, выполнение проверки чисел в виде строки) можно легко превратить в функции, которые можно повторно использовать в самых разных ситуациях.

Теги

C++ / CppiostreamLearnCppstd::cinstd::iosSTL / Standard Template Library / Стандартная библиотека шаблоновВалидацияВвод/выводДля начинающихОбучениеПрограммирование

���������� � ���������� ����������� ������� �����/������ ���

����� ���������������� ��������������� ���� ��� �������� �������

������. ����������� �������� �����/������ ���������������

������������� ��� ���������� ����� ���������� ����� ������. ������

� C++ ���������� ������ ������������ ����� �����, ������������

�������������, � ����� ������������ ���� � ����� ����� � ��������

���� �����. ��������, �������� �����/������ ������ ���� �������,

�������, �������� � ������������, ����������� � ������, � �� �����

������� ������. ����� ������� ��� �� ������ ������� ����, ������� �

������������ ������ ���� ����������� �������� ��������������

�������� �����/������ � ��������� ����������� �������� �����/������

������������� � ����������� ����������.

C++ ���������� ���, ����� � ������������ ���� �����������

���������� ����� ���� ����� �� ����������� � �������, ����� �

���������� ����. ������� ������������ �������� ���������� ����, ���

�������� �����/������ ��� C++ ������ �������������� � C++ �

����������� ������ ��� �������, ������� �������� �������

������������. ����������� ����� �������� �����/������ ������������

����� ������� �������� �� ���� �����.

�������� �����/������ ������� ������������� �

���������� �������������� �������������� �������� �

������������������ �������� � �������. ���� � ������ �����

�����/������, �� ��� �������� ���������������� � ������� UNIX, �

������� ����� ����� ��������� �����/������ �������������� �����

������������ ������� ������ ��� ����� ���, ��� ���� ���

������������ ����� � ��������� ������������. ����� ��� ������������

�������� �������� ����������� � ������� ������������ �����

�������������� �������� � ������������� �� �������������� �������.

��������� � ���������� � ������������ ������������� �����

���������� ������� � � ��������� ���� ����������� � ������� ������

�������������� ����� ������� ��� ������ ������� ������. ��������:

put(cerr,"x = "); // cerr - ����� ������ ������ put(cerr,x); put(cerr,"n");

��� ��������� ���������� ��, ����� �� ������� put ����� ����������

��� ������� ���������. ��� ������� ����������� � ���������� ������.

������ ��� ��������� ������������. ���������� �������� << ���������

«��������� �» ���� ����� ������� ������ � ��������� ������������

�������� ��� �������� ����� ����������. ��������:

cerr << "x = " << x << "n";

��� cerr — ����������� ����� ������ ������. �������, ���� x

�������� int �� ��������� 123, �� ���� �������� ���������� �

����������� ����� ������ ������

x = 123

� ������ ����� ������. ����������, ���� X ����������� �������������

������������� ���� complex � ����� �������� (1,2.4), �� �����������

���� �������� ���������� � cerr

x = 1,2.4)

���� ����� ����� ��������� ������, ����� ��� x ����������

�������� <<, � ������������ ����� ���������� �������� << ��� ������

����.

8.2.2 ��������� ����������� ����������

�������� ������ ������������, ����� �������� ��� ��������������,

������� ���� �� ������������� ������� ������. �� ������ < ����������� ��������� ����� ����������� ������ ��� (#6.2).

�������� ������������ ���� ���������� ������������ � �� ����, � ��

�����, �� �����������, ����������� ����� ������������, �����

�������� ����� ���������� �� �������� ������. ����� ����, = �� � ��

������� ����������� (�������������), �� ���� cout=a=b ��������

cout=(a=b).

�������� ������� ������������ �������� < � >, �� ��������

«������» � «������» ��������� ������ ������ � �������� �����, ���

����� �������� �����/������ �� ���� �������� ������� ���������

�����������. ������ �����, «<» ��������� �� ����������� ���������

��� ��� �� «,», � � ����� ���������� ��������� ����� ������:

cout < x , y , z;

��� ����� ���������� �������� ������ ������� ��������� �� �������.

�������� << � >> � ������ ���� ��������� �� ��������, ���

������������ � ��� ������, ��� �� ����� ���������������� � «�» �

«��», � ��������� << ���������� �����, ����� ����� ���� ��

������������ ������ ��� �������������� ��������� � ���� ���������.

��������:

cout << "a*b+c=" << a*b+c << "n";

�����������, ��� ��������� ���������, ������� �������� �������� �

����� ������� ������������, ������ ������������ ����. ��������:

cout << "a^b|c=" << (a^b|c) << "n";

�������� ������ ������ ���� ����� ��������� � ��������� ������:

cout << "a<

8.2.3 ��������������� �����

���� << ����������� ������ ��� ������������������ ������, � ��

����� ���� � �������� ���������� ��� ������ ��� ����� �������

������� � �����������. ������ ����� ���������� ����� ���������

������������� �������, ��������� ������������� ������ ��������� �

���� ������, ������� ������������ ��� ������. �� ������

(��������������) �������� ���������, ������� ���������� �������

������ ��������������.

char* oct(long, int =0); // ������������ ������������� char* dec(long, int =0); // ���������� ������������� char* hex(long, int =0); // ����������������� ������������� char* chr(int, int =0); // ������ char* str(char*, int =0); // ������

���� �� ������ ���� ������� �����, �� ����� ������������� ��������

��� ����������; ����� ����� �������������� ������� ��������

(�����), ������� �����. ��������:

cout << "dec(" << x

<< ") = oct(" << oct(x,6)

<< ") = hex(" << hex(x,4)

<< ")";

���� x==15, �� � ���������� ���������:

dec(15) = oct( 17) = hex( f);

����� ����� ������������ ������ � ����� �������:

char* form(char* format ...); cout<

8.3.3 �������� ������

������ ������ ����, ��� ����������� � ����������� �����,

����������� � ������ ������������ �������� � ����� �������� ��

�����������. ��������� ����� ��������� ����������

�������� cin, cout � cerr, �� ������ (���� �� �� ����) ����������

�� ����� ������� ��� ��� �������� ������. ���, ������, ���������,

������� ��������� ��� �����, �������� ��� ��������� ���������

������, � �������� ������ �� ������:

#include

void error(char* s, char* s2)

{

cerr << s << " " << s2 << "n";

exit(1);

}

main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

if (argc != 3) error("�������� ����� ����������","");

filebuf f1;

if (f1.open(argv[1],input) == 0)

error("�� ���� ������� ������� ����",argv[1]);

istream from(&f1);

filebuf f2;

if (f2.open(argv[2],output) == 0)

error("�� ���� ������� �������� ����",argv[2]);

ostream to(&f2);

char ch;

while (from.get(ch)) to.put(ch);

if (!from.eof() !! to.bad())

error("��������� ����� ��������","");

}

������������������ �������� ��� �������� ostream ��� ������������

����� �� ��, ��� ������������ ��� ����������� �������: (1) �������

��������� ����� (����� ��� �������� ����������� �������� filebuf);

(2) ����� � ���� �������������� ���� (����� ��� ��������

����������� �������� ����� � ������� ������� filebuf::open()); �,

�������, (3) ��������� ��� ostream � filebuf � �������� ���������.

������ ����� �������������� ����������.

���� ����� ����������� � ����� �� ���� ���:

enum open_mode { input, output };

�������� filebuf::open() ���������� 0, ���� �� ����� ������� ���� �

������������ � �����������. ���� ������������ �������� �������

����, �������� �� ���������� ��� output, �� ����� ������.

����� ����������� ��������� ���������, ��������� �� ������ �

���������� ��������� (��.

����� istream ������������ ���:

class istream {

// ...

public:

istream& operator>>(char*); // ������

istream& operator>>(char&); // ������

istream& operator>>(short&);

istream& operator>>(int&);

istream& operator>>(long&);

istream& operator>>(float&);

istream& operator>>(double&);

// ...

};

������� ����� ������������ � ����� ����:

istream& istream::operator>>(char& c);

{

// ���������� ��������

int a;

// ����� ������� ������ ������ � "a"

c = a;

}

������� ������������ ��� ����������� ������� � C, ����� �����

isspase() � ��� ����, ��� ��� ���������� � (������,

���������, ������ ����� ������, ������� ������� � ������� �������).

� �������� ������������ ����� ������������ ������� get():

class istream {

// ...

istream& get(char& c); // char

istream& get(char* p, int n, int ='n'); // ������

};

��� ������������ ������� �������� ��� ��, ��� ��������� �������.

������� istream::get(char) ������ ���� � ��� �� ������ � ����

��������; ������ istream::get ������ �� ����� n �������� � ������

��������, ������������ � p. �������������� ������ ��������

������������ ��� ������� ������� ��������� (�����, ����������� ���

������������), �� ���� ���� ������ �������� �� �����. ���� �����

�������� ������ ������������, �� ��������� ��� ������ ������

������. �� ��������� ������ ������� get ����� ������ ����� �������

n ��������, �� �� ������ ��� ���� ������, ‘n’ ��������

������������� �� ���������. �������������� ������ �������� ������

������, ������� �������� �� �����. ��������:

cin.get(buf,256,'t');

����� ������ � buf �� ����� 256 ��������, � ���� ����������

��������� (‘t’), �� ��� �������� � �������� �� get. � ���� ������

��������� ��������, ������� ����� ������ �� cin, ����� ‘t’.

����������� ������������ ���� ���������� ���������

�������, ������� ����� ��������� ��������� ��� ������������� �����:

int isalpha(char) // 'a'..'z' 'A'..'Z'

int isupper(char) // 'A'..'Z'

int islower(char) // 'a'..'z'

int isdigit(char) // '0'..'9'

int isxdigit(char) // '0'..'9' 'a'..'f' 'A'..'F'

int isspase(char) // ' ' 't' ������� ����� ������

// ������� �������

int iscntrl(char) // ����������� ������

// (ASCII 0..31 � 127)

int ispunct(char) // ����������: ������ �� �����������������

int isalnum(char) // isalpha() | isdigit()

int isprint(char) // ����������: ascii ' '..'-'

int isgraph(char) // isalpha() | isdigit() | ispunct()

int isascii(char c) { return 0<=c &&c<=127; }

��� ����� isascii() ����������� ������ ���������, � �����������

������� � �������� ������� � ������� ��������� ��������. �������

����� ���������, ���

(('a'<=c && c<='z') || ('A'<=c && c<='Z')) // ����������

�� ������ ����������� ������� � ������� �������� (�� ������ �

������� �������� EBCDIC ��� ����� ��������� ������������ �������),

��� ����� � ����� ����������, ��� ���������� ����������� �������:

isalpha(c)

8.4.2 ��������� ������

������ ����� (istream ��� ostream) ����� ��������������� � ���

���������, � ��������� ������ � ������������� �������

�������������� � ������� ��������������� ��������� � �������� �����

���������.

����� ����� ���������� � ����� �� ��������� ���������:

enum stream_state { _good, _eof, _fail, _bad };

���� ��������� _good ��� _eof, ������ ��������� �������� �����

������ �������. ���� ��������� _good, �� ��������� �������� �����

����� ������ �������, � ��������� ������ ��� ���������� ��������.

������� �������, ���������� �������� ����� � ������, ������� ��

��������� � ��������� _good, �������� ������ ���������. ����

�������� ������� ������ � ���������� v, � �������� ������������

��������, �������� v ������ �������� ���������� (��� �����

����������, ���� v ����� ���� �� ��� �����, ������� ��������������

��������� ������� istream ��� ostream). ������� ����� �����������

_fail � _bad ����� ������������� � ������������ ������� ������ ���

������������� �������� �����. � ��������� _fail ��������������, ���

����� �� �������� � ������� ������� �� ��������. � ��������� _bad

����� ���� ��� ��� ������.

��������� ������ ����� ��������� �������� ���:

switch (cin.rdstate()) {

case _good:

// ��������� �������� ��� cin ������ �������

break;

case _eof:

// ����� �����

break;

case _fail:

// ������� ���� ������ ��������������

// ��������, �� ������� ������

break;

case _bad:

// ��������, ������� cin ��������

break;

}

��� ����� ���������� z ����, ��� �������� ���������� �������� <<

� >>, ���������� ���� ����� �������� ���:

while (cin>>z) cout << z << "n";

��������, ���� z — ������ ��������, ���� ���� ����� �����

����������� ���� � �������� ��� � ����������� ����� �� ������ �����

(�� ����, ������������������ �������� ��� �������) �� ������.

����� � �������� ������� ������������ �����, ���������� ��������

��������� ������ � ��� �������� �������� ������� (�� ����,

�������� ������� �� ����) ������ ���� ��������� _good. � ���������,

� ���������� ����� ����������� ��������� istream, �������

���������� cin>>z. ����� ����������, ������ ���� ��� ��������

����������� ��������, ����� ����������� ���������. ����� ��������

������ ����������� ��������� �������������� (

8.4.3 ���� �����, ������������ �������������

���� ��� ����������������� ���� ����� ������������ ����� ��� ��,

��� �����, �� ��� �����������, ��� ��� �������� ����� �����, �����

������ �������� ��� ���������� ����. ��������:

istream& operator>>(istream& s, complex& a)

/*

������� ����� ��� complex; "f" ���������� float:

f

( f )

( f , f )

*/

{

double re = 0, im = 0;

char c = 0;

s >> c;

if (c == '(') {

s >> re >> c;

if (c == ',') s >> im >> c;

if (c != ')') s.clear(_bad); // ���������� state

}

else {

s.putback(c);

s >> re;

}

if (s) a = complex(re,im);

return s;

}

�������� �� ��, ��� �� ������� ���� ��������� ������, �������

����� ����� ������ ��� �� ����� ���� ������������ �����. ���������

���������� c ����������������, ����� �� �������� �� ���������

�������� ‘(‘ ����� ����, ��� �������� ��������� ��������.

����������� �������� ��������� ������ �����������, ��� ��������

��������� a ����� ���������� ������ � ��� ������, ���� ��� ����

������.

�������� ��������� ��������� ������� clear() (��������), ������

��� ��� ���� ����� ������������ ��� ��������� ��������� ������

������ ��� _good. _good �������� ��������� ��������� �� ��������� �

��� istream::clear(), � ��� ostream::clear().

��� ���������� ����� ���� ���������� ���. ���� ��, � ���������,

������������, ���� �� ����� ���� �������� ���� � �������� �������

(��� � ������ ������ � ����), � ����� ���������, ������ �� �������

��� �������� �����. ����� �������� ������ ���� ��, �������,

������������ ��������� �������������� �����������, ����� ��� �����

��������������� ����� ����� � ��� �������� ��������� ����� ���������

������� �������������.

8.4.4 ������������� ������� �����

�����������, ��� istream, ��� �� ��� � ostream, �������

�������������:

class istream {

// ...

istream(streambuf* s, int sk =1, ostream* t =0);

istream(int size, char* p, int sk =1);

istream(int fd, int sk =1, ostream* t =0);

};

�������� sk ������, ������ ������������ �������� ��� ���. ��������

t (��������������) ������ ��������� �� ostream, � ��������

���������� istream. ��������, cin ���������� � cout; ��� ������,

��� ����� ���, ��� ���������� ������ ������� �� ������ �����, cin

���������

cout.flush(); // ����� ����� ������

� ������� ������� istream::tie() ����� ���������� (��� ���������,

� ������� tie(0)) ����� ostream � ������ istream. ��������:

int y_or_n(ostream& to, istream& from)

/*

"to", �������� ������ �� "from"

*/

{

ostream* old = from.tie(&to);

for (;;) {

cout << "�������� Y ��� N: ";

char ch = 0;

if (!cin.get(ch)) return 0;

if (ch != 'n') { // ���������� ������� ������

char ch2 = 0;

while (cin.get(ch2) && ch2 != 'n') ;

}

switch (ch) {

case 'Y':

case 'y':

case 'n':

from.tie(old); // ��������������� ������ tie

return 1;

case 'N':

case 'n':

from.tie(old); // ��������������� ������ tie

return 0;

default:

cout << "��������, ���������� ��� ���: ";

}

}

}

����� ������������ �������������� ���� (��� ��� ���������� ��

���������), ������������ �� ����� ������ ������ ���� ����� �������

�������. ������� ���� ��������� ������� ����� ������. y_or_n()

������� �� ������ ������ ������, � ��������� ����������.

������ ����� ������� � ����� � ������� �������

istream::putback(char). ��� ��������� ��������� «�����������

������» � ����� �����.

8.5 ������ �� ��������

����� ������������ ��������, �������� �����/������, ���

���������� ��������, ���������� � ���� istream ��� ostream.

��������, ���� ������ �������� ������� ������, ������������� �����,

��� ������ ���� �� ����� ������� ����� ������������ �����������

���� ���������� ����:

void word_per_line(char v[], int sz)

/*

������� "v" ������� "sz" �� ������ ����� �� ������

*/

{

istream ist(sz,v); // ������� istream ��� v

char b2[MAX]; // ������ ����������� �����

while (ist>>b2) cout << b2 << "n";

}

����������� ������� ������ � ���� ������ ���������������� ���

������ ����� �����.

� ������� ostream ����� ��������������� ���������, ������� ��

����� �������� ������ ��:

char* p = new char[message_size]; ostream ost(message_size,p); do_something(arguments,ost); display(p);

����� ��������, ��� do_something, ����� ������ � ����� ost,

���������� ost ����� ������������ � �.�. � ������� �����������

�������� ������. ��� ������������� ������ �������� �� ������������,

��������� ost ����� ���� ����� � ����� �� ����� �������������, ��

����� ���������� � ��������� _fail. �, �������, display �����

������ ��������� � «���������» ����� ������. ���� ����� �����

��������� �������� ��������, ����� ����������� � ����������, �

������� ������������� ����������� ������ �������� � ���� �����

����� �������, ��� ������ � ������������ ���������� �����������

������. ��������, ����� �� ost ��� �� ���������� � ���������������

���-�� �� ������ ������� �������������� �������.

8.6 �����������

��� ������� �������� �����/������ �� ����� �� �������� �����

������, �� ���� �� ��� ���������� ����� ������������� ��������� �

����� ������ ��������� �����������. ��������, ��� ostream,

������������� � ���������� ������, ��������� ����������� �������

����, ������ ��� ostream, ������������� � �����. � ����� ����������

����� ����������, ������� ��������� �������� ���� ��� ������

������� � ������ ������������� (�������� �������� �� ���

������������ ������ ostream). ���� ������ ���� ����� �������� ���

����� ��������� ������, ������� � �������� ostream ��� ����, ��

������������. ������ �������, ������� ������������ ������������

������ � �����, �����������. ����� ����������, ����� ����������� �

����������� � ������ ����� ���������� �����������. ��� ����� ������

������� �������� ���������� ����������� ������� ��� ����, �����

������� ��������� ���������� ��������� ��������� �������������

������� � ��������� �����������. �������� ������ ������ �

�������� ���:

struct streambuf { // ���������� ������� ������

char* base; // ������ ������

char* pptr; // ��������� ��������� char

char* qptr; // ��������� ����������� char

char* eptr; // ���� �� ������ ������

char alloc; // �����, ���������� � ������� new

// ���������� �����:

// ���������� EOF ��� ������ � 0 � ������ ������

virtual int overflow(int c =EOF);

// ��������� �����

// ��������� EOF ��� ������ ��� ����� �����,

// ����� ��������� char

virtual int underflow();

int snextc() // ����� ��������� char

{

return (++qptr==pptr) ? underflow() : *qptr&0377;

}

// ...

int allocate() // �������� ��������� ������������ ������

streambuf() { /* ... */}

streambuf(char* p, int l) { /* ... */}

~streambuf() { /* ... */}

};

�������� ��������, ��� ����� ������������ ���������, �����������

��� ������ � �������, ������� ������� ������������ �������� �����

���������� (������ ���� ���) � ���� ����������� ����������� inline-

�������. ��� ������ ���������� ��������� ����������� ����������

���������� ������ ������� ������������ overflow() � underflow().

��������:

struct filebuf : public streambuf {

int fd; // ���������� �����

char opened; // ���� ������

int overflow(int c =EOF);

int underflow();

// ...

// ��������� ����:

// ���� �� �����������, �� ���������� 0,

// � ������ ������ ���������� "this"

filebuf* open(char *name, open_mode om);

int close() { /* ... */ }

filebuf() { opened = 0; }

filebuf(int nfd) { /* ... */ }

filebuf(int nfd, char* p, int l) : (p,l) { /* ... */ }

~filebuf() { close(); }

};

int filebuf::underflow() // ��������� ����� �� fd

{

if (!opened || allocate()==EOF) return EOF;

int count = read(fd, base, eptr-base);

if (count < 1) return EOF;

qptr = base;

pptr = base + count;

return *qptr & 0377;

}

В C++ различают ошибки времени компиляции и ошибки времени выполнения. Ошибки первого типа обнаруживает компилятор до запуска программы. К ним относятся, например, синтаксические ошибки в коде. Ошибки второго типа проявляются при запуске программы. Примеры ошибок времени выполнения: ввод некорректных данных, некорректная работа с памятью, недостаток места на диске и т. д. Часто такие ошибки могут привести к неопределённому поведению программы.

Некоторые ошибки времени выполнения можно обнаружить заранее с помощью проверок в коде. Например, такими могут быть ошибки, нарушающие инвариант класса в конструкторе. Обычно, если ошибка обнаружена, то дальнейшее выполение функции не имеет смысла, и нужно сообщить об ошибке в то место кода, откуда эта функция была вызвана. Для этого предназначен механизм исключений.

Коды возврата и исключения

Рассмотрим функцию, которая считывает со стандартного потока возраст и возвращает его вызывающей стороне. Добавим в функцию проверку корректности возраста: он должен находиться в диапазоне от 0 до 128 лет. Предположим, что повторный ввод возраста в случае ошибки не предусмотрен.

int ReadAge() {

int age;

std::cin >> age;

if (age < 0 || age >= 128) {

// Что вернуть в этом случае?

}

return age;

}

Что вернуть в случае некорректного возраста? Можно было бы, например, договориться, что в этом случае функция возвращает ноль. Но тогда похожая проверка должна быть и в месте вызова функции:

int main() {

if (int age = ReadAge(); age == 0) {

// Произошла ошибка

} else {

// Работаем с возрастом age

}

}

Такая проверка неудобна. Более того, нет никакой гарантии, что в вызывающей функции программист вообще её напишет. Фактически мы тут выбрали некоторое значение функции (ноль), обозначающее ошибку. Это пример подхода к обработке ошибок через коды возврата. Другим примером такого подхода является хорошо знакомая нам функция main. Только она должна возвращать ноль при успешном завершении и что-либо ненулевое в случае ошибки.

Другим способом сообщить об обнаруженной ошибке являются исключения. С каждым сгенерированным исключением связан некоторый объект, который как-то описывает ошибку. Таким объектом может быть что угодно — даже целое число или строка. Но обычно для описания ошибки заводят специальный класс и генерируют объект этого класса:

#include <iostream>

struct WrongAgeException {

int age;

};

int ReadAge() {

int age;

std::cin >> age;

if (age < 0 || age >= 128) {

throw WrongAgeException(age);

}

return age;

}

Здесь в случае ошибки оператор throw генерирует исключение, которое представлено временным объектом типа WrongAgeException. В этом объекте сохранён для контекста текущий неправильный возраст age. Функция досрочно завершает работу: у неё нет возможности обработать эту ошибку, и она должна сообщить о ней наружу. Поток управления возвращается в то место, откуда функция была вызвана. Там исключение может быть перехвачено и обработано.

Перехват исключения

Мы вызывали нашу функцию ReadAge из функции main. Обработать ошибку в месте вызова можно с помощью блока try/catch:

int main() {

try {

age = ReadAge(); // может сгенерировать исключение

// Работаем с возрастом age

} catch (const WrongAgeException& ex) { // ловим объект исключения

std::cerr << "Age is not correct: " << ex.age << "n";

return 1; // выходим из функции main с ненулевым кодом возврата

}

// ...

}

Мы знаем заранее, что функция ReadAge может сгенерировать исключение типа WrongAgeException. Поэтому мы оборачиваем вызов этой функции в блок try. Если происходит исключение, для него подбирается подходящий catch-обработчик. Таких обработчиков может быть несколько. Можно смотреть на них как на набор перегруженных функций от одного аргумента — объекта исключения. Выбирается первый подходящий по типу обработчик и выполняется его код. Если же ни один обработчик не подходит по типу, то исключение считается необработанным. В этом случае оно пробрасывается дальше по стеку — туда, откуда была вызвана текущая функция. А если обработчик не найдётся даже в функции main, то программа аварийно завершается.

Усложним немного наш пример, чтобы из функции ReadAge могли вылетать исключения разных типов. Сейчас мы проверяем только значение возраста, считая, что на вход поступило число. Но предположим, что поток ввода досрочно оборвался, или на входе была строка вместо числа. В таком случае конструкция std::cin >> age никак не изменит переменную age, а лишь возведёт специальный флаг ошибки в объекте std::cin. Наша переменная age останется непроинициализированной: в ней будет лежать неопределённый мусор. Можно было бы явно проверить этот флаг в объекте std::cin, но мы вместо этого включим режим генерации исключений при таких ошибках ввода:

int ReadAge() {

std::cin.exceptions(std::istream::failbit);

int age;

std::cin >> age;

if (age < 0 || age >= 128) {

throw WrongAgeException(age);

}

return age;

}

Теперь ошибка чтения в операторе >> у потока ввода будет приводить к исключению типа std::istream::failure. Функция ReadAge его не обрабатывает. Поэтому такое исключение покинет пределы этой функции. Поймаем его в функции main:

int main() {

try {

age = ReadAge(); // может сгенерировать исключения разных типов

// Работаем с возрастом age

} catch (const WrongAgeException& ex) {

std::cerr << "Age is not correct: " << ex.age << "n";

return 1;

} catch (const std::istream::failure& ex) {

std::cerr << "Failed to read age: " << ex.what() << "n";

return 1;

} catch (...) {

std::cerr << "Some other exceptionn";

return 1;

}

// ...

}

При обработке мы воспользовались функцией ex.what у исключения типа std::istream::failure. Такие функции есть у всех исключений стандартной библиотеки: они возвращают текстовое описание ошибки.

Обратите внимание на третий catch с многоточием. Такой блок, если он присутствует, будет перехватывать любые исключения, не перехваченные ранее.

Исключения стандартной библиотеки

Функции и классы стандартной библиотеки в некоторых ситуациях генерируют исключения особых типов. Все такие типы выстроены в иерархию наследования от базового класса std::exception. Иерархия классов позволяет писать обработчик catch сразу на группу ошибок, которые представлены базовым классом: std::logic_error, std::runtime_error и т. д.

Вот несколько примеров:

-

Функция

atу контейнеровstd::array,std::vectorиstd::dequeгенерирует исключениеstd::out_of_rangeпри некорректном индексе. -

Аналогично, функция

atуstd::map,std::unordered_mapи у соответствующих мультиконтейнеров генерирует исключениеstd::out_of_rangeпри отсутствующем ключе. -

Обращение к значению у пустого объекта

std::optionalприводит к исключениюstd::bad_optional_access. -

Потоки ввода-вывода могут генерировать исключение

std::ios_base::failure.

Исключения в конструкторах

В главе 3.1 мы написали класс Time. Этот класс должен был соблюдать инвариант на значение часов, минут и секунд: они должны были быть корректными. Если на вход конструктору класса Time передавались некорректные значения, мы приводили их к корректным, используя деление с остатком.

Более правильным было бы сгенерировать в конструкторе исключение. Таким образом мы бы явно передали сообщение об ошибке во внешнюю функцию, которая пыталась создать объект.

class Time {

private:

int hours, minutes, seconds;

public:

// Заведём класс для исключения и поместим его внутрь класса Time как в пространство имён

class IncorrectTimeException {

};

Time::Time(int h, int m, int s) {

if (s < 0 || s > 59 || m < 0 || m > 59 || h < 0 || h > 23) {

throw IncorrectTimeException();

}

hours = h;

minutes = m;

seconds = s;

}

// ...

};

Генерировать исключения в конструкторах — совершенно нормальная практика. Однако не следует допускать, чтобы исключения покидали пределы деструкторов. Чтобы понять причины, посмотрим подробнее, что происходит при генерации исключения.

Свёртка стека

Вспомним класс Logger из предыдущей главы. Посмотрим, как он ведёт себя при возникновении исключения. Воспользуемся в этом примере стандартным базовым классом std::exception, чтобы не писать свой класс исключения.

#include <exception>

#include <iostream>

void f() {

std::cout << "Welcome to f()!n";

Logger x;

// ...

throw std::exception(); // в какой-то момент происходит исключение

}

int main() {

try {

Logger y;

f();

} catch (const std::exception&) {

std::cout << "Something happened...n";

return 1;

}

}

Мы увидим такой вывод:

Logger(): 1 Welcome to f()! Logger(): 2 ~Logger(): 2 ~Logger(): 1 Something happened...

Сначала создаётся объект y в блоке try. Затем мы входим в функцию f. В ней создаётся объект x. После этого происходит исключение. Мы должны досрочно покинуть функцию. В этот момент начинается свёртка стека (stack unwinding): вызываются деструкторы для всех созданных объектов в самой функции и в блоке try, как если бы они вышли из своей области видимости. Поэтому перед обработчиком исключения мы видим вызов деструктора объекта x, а затем — объекта y.

Аналогично, свёртка стека происходит и при генерации исключения в конструкторе. Напишем класс с полем Logger и сгенерируем нарочно исключение в его конструкторе:

#include <exception>

#include <iostream>

class C {

private:

Logger x;

public:

C() {

std::cout << "C()n";

Logger y;

// ...

throw std::exception();

}

~C() {

std::cout << "~C()n";

}

};

int main() {

try {

C c;

} catch (const std::exception&) {

std::cout << "Something happened...n";

}

}

Вывод программы:

Logger(): 1 // конструктор поля x C() Logger(): 2 // конструктор локальной переменной y ~Logger(): 2 // свёртка стека: деструктор y ~Logger(): 1 // свёртка стека: деструктор поля x Something happened...

Заметим, что деструктор самого класса C не вызывается, так как объект в конструкторе не был создан.

Механизм свёртки стека гарантирует, что деструкторы для всех созданных автоматических объектов или полей класса в любом случае будут вызваны. Однако он полагается на важное свойство: деструкторы самих классов не должны генерировать исключений. Если исключение в деструкторе произойдёт в момент свёртки стека при обработке другого исключения, то программа аварийно завершится.

Пример с динамической памятью

Подчеркнём, что свёртка стека работает только с автоматическими объектами. В этом нет ничего удивительного: ведь за временем жизни объектов, созданных в динамической памяти, программист должен следить самостоятельно. Исключения вносят дополнительные сложности в ручное управление динамическими объектами:

void f() {

Logger* ptr = new Logger(); // конструируем объект класса Logger в динамической памяти

// ...

g(); // вызываем какую-то функцию

// ...

delete ptr; // вызываем деструктор и очищаем динамическую память

}

На первый взгляд кажется, что в этом коде нет ничего опасного: delete вызывается в конце функции. Однако функция g может сгенерировать исключение. Мы не перехватываем его в нашей функции f. Механизм свёртки уберёт со стека лишь сам указатель ptr, который является автоматической переменной примитивного типа. Однако он ничего не сможет сделать с объектом в памяти, на которую ссылается этот указатель. В логе мы увидим только вызов конструктора класса Logger, но не увидим вызова деструктора. Нам придётся обработать исключение вручную:

void f() {

Logger* ptr = new Logger();

// ...

try {

g();

} catch (...) { // ловим любое исключение

delete ptr; // вручную удаляем объект

throw; // перекидываем объект исключения дальше

}

// ...

delete ptr;

}

Здесь мы перехватываем любое исключение и частично обрабатываем его, удаляя объект в динамической памяти. Затем мы прокидываем текущий объект исключения дальше с помощью оператора throw без аргументов.

Согласитесь, этот код очень далёк от совершенства. При непосредственной работе с объектами в динамической памяти нам приходится оборачивать в try/catch любую конструкцию, из которой может вылететь исключение. Понятно, что такой код чреват ошибками. В главе 3.6 мы узнаем, как с точки зрения C++ следует работать с такими ресурсами, как память.

Гарантии безопасности исключений

Предположим, что мы пишем свой класс-контейнер, похожий на двусвязный список. Наш контейнер позволяет добавлять элементы в хранилище и отдельно хранит количество элементов в некотором поле elementsCount. Один из инвариантов этого класса такой: значение elementsCount равно реальному числу элементов в хранилище.

Не вдаваясь в детали, давайте посмотрим, как могла бы выглядеть функция добавления элемента.

template <typename T>

class List {

private:

struct Node { // узел двусвязного списка

T element;

Node* prev = nullptr; // предыдущий узел

Node* next = nullptr; // следующий узел

};

Node* first = nullptr; // первый узел списка

Node* last = nullptr; // последний узел списка

int elementsCount = 0;

public:

// ...

size_t Size() const {

return elementsCount;

}

void PushBack(const T& elem) {

++elementsCount;

// Конструируем в динамической памяти новой узел списка

Node* node = new Node(elem, last, nullptr);

// Связываем новый узел с остальными узлами

if (last != nullptr) {

last->next = node;

} else {

first = node;

}

last = node;

}

};

Не будем здесь рассматривать другие функции класса — конструкторы, деструктор, оператор присваивания… Рассмотрим функцию PushBack. В ней могут произойти такие исключения:

-

Выражение

newможет сгенерировать исключениеstd::bad_allocиз-за нехватки памяти. -

Конструктор копирования класса

Tможет сгенерировать произвольное исключение. Этот конструктор вызывается при инициализации поляelementсоздаваемого узла в конструкторе классаNode. В этом случаеnewведёт себя как транзакция: выделенная перед этим динамическая память корректно вернётся системе.

Эти исключения не перехватываются в функции PushBack. Их может перехватить код, из которого PushBack вызывался:

#include <iostream>

class C; // какой-то класс

int main() {

List<C> data;

C element;

try {

data.PushBack(element);

} catch (...) { // не получилось добавить элемент

std::cout << data.Size() << "n"; // внезапно 1, а не 0

}

// работаем дальше с data

}

Наша функция PushBack сначала увеличивает счётчик элементов, а затем выполняет опасные операции. Если происходит исключение, то в классе List нарушается инвариант: значение счётчика elementsCount перестаёт соответствовать реальности. Можно сказать, что функция PushBack не даёт гарантий безопасности.

Всего выделяют четыре уровня гарантий безопасности исключений (exception safety guarantees):

-

Гарантия отсутствия сбоев. Функции с такими гарантиями вообще не выбрасывают исключений. Примерами могут служить правильно написанные деструктор и конструктор перемещения, а также константные функции вида

Size. -

Строгая гарантия безопасности. Исключение может возникнуть, но от этого объект нашего класса не поменяет состояние: количество элементов останется прежним, итераторы и ссылки не будут инвалидированы и т. д.

-

Базовая гарантия безопасности. При исключении состояние объекта может поменяться, но оно останется внутренне согласованным, то есть, инварианты будут соблюдаться.

-

Отсутсвие гарантий. Это довольно опасная категория: при возникновении исключений могут нарушаться инварианты.

Всегда стоит разрабатывать классы, обеспечивающие хотя бы базовую гарантию безопасности. При этом не всегда возможно эффективно обеспечить строгую гарантию.

Переместим в нашей функции PushBack изменение счётчика в конец:

void PushBack(const T& elem) {

Node* node = new Node(elem, last, nullptr);

if (last != nullptr) {

last->next = node;

} else {

first = node;

}

last = node;

++elementsCount; // выполнится только если раньше не было исключений

}

Теперь такая функция соответствует строгой гарантии безопасности.

В документации функций из классов стандартной библиотеки обычно указано, какой уровень гарантии они обеспечивают. Рассмотрим, например, гарантии безопасности класса std::vector.

-

Деструктор, функции

empty,size,capacity, а такжеclearпредоставляют гарантию отсутствия сбоев. -

Функции

push_backиresizeпредоставляют строгую гарантию. -

Функция

insertпредоставляет лишь базовую гарантию. Можно было бы сделать так, чтобы она предоставляла строгую гарантию, но за это пришлось бы заплатить её эффективностью: при вставке в середину вектора пришлось бы делать реаллокацию.

Функции класса, которые гарантируют отсутсвие сбоев, следует помечать ключевым словом noexcept:

class C {

public:

void f() noexcept {

// ...

}

};

С одной стороны, эта подсказка позволяет компилятору генерировать более эффективный код. С другой — эффективно обрабатывать объекты таких классов в стандартных контейнерах. Например, std::vector<C> при реаллокации будет использовать конструктор перемещения класса C, если он помечен как noexcept. В противном случае будет использован конструктор копирования, который может быть менее эффективен, но зато позволит обеспечить строгую гарантию безопасности при реаллокации.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about standard I/O file descriptors. For System V streams, see STREAMS.

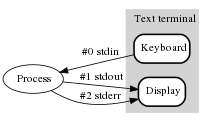

In computer programming, standard streams are interconnected input and output communication channels[1] between a computer program and its environment when it begins execution. The three input/output (I/O) connections are called standard input (stdin), standard output (stdout) and standard error (stderr). Originally I/O happened via a physically connected system console (input via keyboard, output via monitor), but standard streams abstract this. When a command is executed via an interactive shell, the streams are typically connected to the text terminal on which the shell is running, but can be changed with redirection or a pipeline. More generally, a child process inherits the standard streams of its parent process.

Application[edit]

The standard streams for input, output, and error

Users generally know standard streams as input and output channels that handle data coming from an input device, or that write data from the application. The data may be text with any encoding, or binary data.

In many modern systems, the standard error stream of a program is redirected into a log file, typically for error analysis purposes.

Streams may be used to chain applications, meaning that the output stream of one program can be redirected to be the input stream to another application. In many operating systems this is expressed by listing the application names, separated by the vertical bar character, for this reason often called the pipeline character. A well-known example is the use of a pagination application, such as more, providing the user control over the display of the output stream on the display.

Background[edit]

In most operating systems predating Unix, programs had to explicitly connect to the appropriate input and output devices. OS-specific intricacies caused this to be a tedious programming task. On many systems it was necessary to obtain control of environment settings, access a local file table, determine the intended data set, and handle hardware correctly in the case of a punch card reader, magnetic tape drive, disk drive, line printer, card punch, or interactive terminal.

One of Unix’s several groundbreaking advances was abstract devices, which removed the need for a program to know or care what kind of devices it was communicating with[citation needed]. Older operating systems forced upon the programmer a record structure and frequently non-orthogonal data semantics and device control. Unix eliminated this complexity with the concept of a data stream: an ordered sequence of data bytes which can be read until the end of file. A program may also write bytes as desired and need not, and cannot easily declare their count or grouping.

Another Unix breakthrough was to automatically associate input and output to terminal keyboard and terminal display, respectively, by default[citation needed] — the program (and programmer) did absolutely nothing to establish input and output for a typical input-process-output program (unless it chose a different paradigm). In contrast, previous operating systems usually required some—often complex—job control language to establish connections, or the equivalent burden had to be orchestrated by the program.[citation needed]

Since Unix provided standard streams, the Unix C runtime environment was obliged to support it as well. As a result, most C runtime environments (and C’s descendants), regardless of the operating system, provide equivalent functionality.

Standard input (stdin)[edit]

Standard input is a stream from which a program reads its input data. The program requests data transfers by use of the read operation. Not all programs require stream input. For example, the dir and ls programs (which display file names contained in a directory) may take command-line arguments, but perform their operations without any stream data input.

Unless redirected, standard input is inherited from the parent process. In the case of an interactive shell, that is usually associated with the keyboard.

The file descriptor for standard input is 0 (zero); the POSIX <unistd.h> definition is STDIN_FILENO; the corresponding C <stdio.h> variable is FILE* stdin; similarly, the C++ <iostream> variable is std::cin.

Standard output (stdout)[edit]

Standard output is a stream to which a program writes its output data. The program requests data transfer with the write operation. Not all programs generate output. For example, the file rename command (variously called mv, move, or ren) is silent on success.

Unless redirected, standard output is inherited from the parent process. In the case of an interactive shell, that is usually the text terminal which initiated the program.

The file descriptor for standard output is 1 (one); the POSIX <unistd.h> definition is STDOUT_FILENO; the corresponding C <stdio.h> variable is FILE* stdout; similarly, the C++ <iostream> variable is std::cout.

Standard error (stderr)[edit]

Standard error is another output stream typically used by programs to output error messages or diagnostics. It is a stream independent of standard output and can be redirected separately.

This solves the semi-predicate problem, allowing output and errors to be distinguished, and is analogous to a function returning a pair of values – see Semi-predicate problem: Multi valued return. The usual destination is the text terminal which started the program to provide the best chance of being seen even if standard output is redirected (so not readily observed). For example, output of a program in a pipeline is redirected to input of the next program or a text file, but errors from each program still go directly to the text terminal so they can be reviewed by the user in real time.[2]

It is acceptable and normal to direct standard output and standard error to the same destination, such as the text terminal. Messages appear in the same order as the program writes them, unless buffering is involved. For example, in common situations the standard error stream is unbuffered but the standard output stream is line-buffered; in this case, text written to standard error later may appear on the terminal earlier, if the standard output stream buffer is not yet full.

The file descriptor for standard error is defined by POSIX as 2 (two); the <unistd.h> header file provides the symbol STDERR_FILENO;[3] the corresponding C <stdio.h> variable is FILE* stderr. The C++ <iostream> standard header provides two variables associated with this stream: std::cerr and std::clog, the former being unbuffered and the latter using the same buffering mechanism as all other C++ streams.

Bourne-style shells allow standard error to be redirected to the same destination that standard output is directed to using

2>&1

csh-style shells allow standard error to be redirected to the same destination that standard output is directed to using

>&

Standard error was added to Unix in the 1970s after several wasted phototypesetting runs ended with error messages being typeset instead of displayed on the user’s terminal.[4]

Timeline[edit]

1950s: Fortran[edit]

Fortran has the equivalent of Unix file descriptors: By convention, many Fortran implementations use unit numbers UNIT=5 for stdin, UNIT=6 for stdout and UNIT=0 for stderr. In Fortran-2003, the intrinsic ISO_FORTRAN_ENV module was standardized to include the named constants INPUT_UNIT, OUTPUT_UNIT, and ERROR_UNIT to portably specify the unit numbers.

! FORTRAN 77 example PROGRAM MAIN INTEGER NUMBER READ(UNIT=5,*) NUMBER WRITE(UNIT=6,'(A,I3)') ' NUMBER IS: ',NUMBER END

! Fortran 2003 example program main use iso_fortran_env implicit none integer :: number read (unit=INPUT_UNIT,*) number write (unit=OUTPUT_UNIT,'(a,i3)') 'Number is: ', number end program

1960: ALGOL 60[edit]

ALGOL 60 was criticized for having no standard file access.[citation needed]

1968: ALGOL 68[edit]

ALGOL 68’s input and output facilities were collectively referred to as the transput.[5] Koster coordinated the definition of the transput standard. The model included three standard channels: stand in, stand out, and stand back.

# ALGOL 68 example # main:( REAL number; getf(stand in,($g$,number)); printf(($"Number is: "g(6,4)"OR "$,number)); # OR # putf(stand out,($" Number is: "g(6,4)"!"$,number)); newline(stand out) ) |

|

| Input: | Output: |

|---|---|

3.14159 |

Number is: +3.142 OR Number is: +3.142! |

1970s: C and Unix[edit]

In the C programming language, the standard input, output, and error streams are attached to the existing Unix file descriptors 0, 1 and 2 respectively.[6] In a POSIX environment the <unistd.h> definitions STDIN_FILENO, STDOUT_FILENO or STDERR_FILENO should be used instead rather than magic numbers. File pointers stdin, stdout, and stderr are also provided.

Ken Thompson (designer and implementer of the original Unix operating system) modified sort in Version 5 Unix to accept «-» as representing standard input, which spread to other utilities and became a part of the operating system as a special file in Version 8. Diagnostics were part of standard output through Version 6, after which Dennis M. Ritchie created the concept of standard error.[7]

1995: Java[edit]

In Java, the standard streams are referred to by System.in (for stdin), System.out (for stdout), and System.err (for stderr).[8]

public static void main(String args[]) { try { BufferedReader br = new BufferedReader(new InputStreamReader(System.in)); String s = br.readLine(); double number = Double.parseDouble(s); System.out.println("Number is:" + number); } catch (Exception e) { System.err.println("Error:" + e.getMessage()); } }

2000s: .NET[edit]

In C# and other .NET languages, the standard streams are referred to by System.Console.In (for stdin), System.Console.Out (for stdout) and System.Console.Error (for stderr).[9] Basic read and write capabilities for the stdin and stdout streams are also accessible directly through the class System.Console (e.g. System.Console.WriteLine() can be used instead of System.Console.Out.WriteLine()).

System.Console.In, System.Console.Out and System.Console.Error are System.IO.TextReader (stdin) and System.IO.TextWriter (stdout, stderr) objects, which only allow access to the underlying standard streams on a text basis. Full binary access to the standard streams must be performed through the System.IO.Stream objects returned by System.Console.OpenStandardInput(), System.Console.OpenStandardOutput() and System.Console.OpenStandardError() respectively.

// C# example public static int Main(string[] args) { try { string s = System.Console.In.ReadLine(); double number = double.Parse(s); System.Console.Out.WriteLine("Number is: {0:F3}", number); return 0; // If Parse() threw an exception } catch (ArgumentNullException) { System.Console.Error.WriteLine("No number was entered!"); } catch (FormatException) { System.Console.Error.WriteLine("The specified value is not a valid number!"); } catch (OverflowException) { System.Console.Error.WriteLine("The specified number is too big!"); } return -1; }

' Visual Basic .NET example Public Function Main() As Integer Try Dim s As String = System.Console.[In].ReadLine() Dim number As Double = Double.Parse(s) System.Console.Out.WriteLine("Number is: {0:F3}", number) Return 0 ' If Parse() threw an exception Catch ex As System.ArgumentNullException System.Console.[Error].WriteLine("No number was entered!") Catch ex2 As System.FormatException System.Console.[Error].WriteLine("The specified value is not a valid number!") Catch ex3 As System.OverflowException System.Console.[Error].WriteLine("The specified number is too big!") End Try Return -1 End Function

When applying the System.Diagnostics.Process class one can use the instance properties StandardInput, StandardOutput, and StandardError of that class to access the standard streams of the process.

2000 — : Python (2 or 3)[edit]

The following example shows how to redirect the standard input both to the standard output

and to a text file.

#!/usr/bin/env python import sys # Save the current stdout so that we can revert sys.stdout # after we complete our redirection stdin_fileno = sys.stdin stdout_fileno = sys.stdout # Redirect sys.stdout to the file sys.stdout = open('myfile.txt', 'w') ctr = 0 for inps in stdin_fileno: ctrs = str(ctr) # Prints to the redirected stdout () sys.stdout.write(ctrs + ") this is to the redirected --->" + inps + 'n') # Prints to the actual saved stdout handler stdout_fileno.write(ctrs + ") this is to the actual --->" + inps + 'n') ctr = ctr + 1 # Close the file sys.stdout.close() # Restore sys.stdout to our old saved file handler sys.stdout = stdout_fileno

GUIs[edit]

Graphical user interfaces (GUIs) don’t always make use of the standard streams; they do when GUIs are wrappers of underlying scripts and/or console programs, for instance the Synaptic package manager GUI, which wraps apt commands in Debian and/or Ubuntu. GUIs created with scripting tools like Zenity and KDialog by KDE project[10] make use of stdin, stdout, and stderr, and are based on simple scripts rather than a complete GUI programmed and compiled in C/C++ using Qt, GTK, or other equivalent proprietary widget framework.

The Services menu, as implemented on NeXTSTEP and Mac OS X, is also analogous to standard streams. On these operating systems, graphical applications can provide functionality through a system-wide menu that operates on the current selection in the GUI, no matter in what application.

Some GUI programs, primarily on Unix, still write debug information to standard error. Others (such as many Unix media players) may read files from standard input. Popular Windows programs that open a separate console window in addition to their GUI windows are the emulators pSX and DOSBox.

GTK-server can use stdin as a communication interface with an interpreted program to realize a GUI.

The Common Lisp Interface Manager paradigm «presents» GUI elements sent to an extended output stream.

See also[edit]

- Redirection (computing)

- Stream (computing)

- Input/output

- C file input/output

- SYSIN and SYSOUT

- Standard streams in OpenVMS

References[edit]

- ^ D. M. Ritchie, «A Stream Input-Output System», AT&T Bell Laboratories Technical Journal, 68(8), October 1984.

- ^ «What are stdin, stdout and stderr in Linux? | CodePre.com». 2 December 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ «<unistd.h>». The Open Group Base Specifications Issue 6—IEEE Std 1003.1, 2004 Edition. The Open Group. 2004.

- ^ Johnson, Steve (2013-12-11). «[TUHS] Graphic Systems C/A/T phototypesetter» (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 2020-09-25. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- ^ Revised

Report on the Algorithmic Language Algol 68, Edited by

A. van Wijngaarden,

B.J. Mailloux,

J.E.L. Peck,

C.H.A. Koster,

M. Sintzoff,

C.H. Lindsey,

L.G.L.T. Meertens

and R.G. Fisker, http://www.softwarepreservation.org/projects/ALGOL/report/Algol68_revised_report-AB.pdf, Section 10.3 - ^ «Stdin(3): Standard I/O streams — Linux man page».

- ^ McIlroy, M. D. (1987). A Research Unix reader: annotated excerpts from the Programmer’s Manual, 1971–1986 (PDF) (Technical report). CSTR. Bell Labs. 139.

- ^ «System (Java Platform SE 7)». Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ^ «C# Reference Source, .NET Framework 4.7.1, mscorlib, Console class». referencesource.microsoft.com. Retrieved 2017-12-10.

- ^ Kißling, Kristian (2009). «Adding graphic elements to your scripts with Zenity and KDialog». Linux Magazine. Retrieved 2021-04-11.

Sources[edit]

- «Standard Streams», The GNU C Library

- KRONOS 2.1 Reference Manual, Control Data Corporation, Part Number 60407000, 1974

- NOS Version 1 Applications Programmer’s Instant, Control Data Corporation, Part Number 60436000, 1978

- Level 68 Introduction to Programming on MULTICS, Honeywell Corporation, 1981

- Evolution of the MVS Operating System, IBM Corporation, 1981

- Lions’ Commentary on UNIX Sixth Edition, John Lions, ISBN 1-57398-013-7, 1977

- Console Class, .NET Framework Class Library, Microsoft Corporation, 2008

External links[edit]

- Standard Input Definition — by The Linux Information Project

- Standard Output Definition — by The Linux Information Project

- Standard Error Definition — by The Linux Information Project

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about standard I/O file descriptors. For System V streams, see STREAMS.

In computer programming, standard streams are interconnected input and output communication channels[1] between a computer program and its environment when it begins execution. The three input/output (I/O) connections are called standard input (stdin), standard output (stdout) and standard error (stderr). Originally I/O happened via a physically connected system console (input via keyboard, output via monitor), but standard streams abstract this. When a command is executed via an interactive shell, the streams are typically connected to the text terminal on which the shell is running, but can be changed with redirection or a pipeline. More generally, a child process inherits the standard streams of its parent process.

Application[edit]

The standard streams for input, output, and error

Users generally know standard streams as input and output channels that handle data coming from an input device, or that write data from the application. The data may be text with any encoding, or binary data.

In many modern systems, the standard error stream of a program is redirected into a log file, typically for error analysis purposes.